6 Essential Guitar Scales (With Pictures)

Published on 11 April 2023

Guitar scales are a powerful key to unlocking your potential as a guitarist. Scales - a collection of notes that produce a particular overall sound - are a direct way for the player to decide how they want their music to sound and feel. You can use scales to make your guitar playing sound happy, sad, exotic or mysterious, just by adhering to each scale’s particular pattern with constructing parts and solos.

Today we’ll start from the basics, showing you a few of the most important scales on the guitar. We’ll keep everything in the key of A for two reasons: firstly, it helps your ear notice the difference in sound from scale to scale when they are all played in the same key; and the key of A puts each scale around the middle of the fingerboard, allowing you to easily move the scale to another key after you’ve learned it. Want to play in the key of C? Easy, just take what you learn today and move everything up 3 frets’ worth. Want to play in G? Move everything down two frets. Simple!

Today’s Mission

Today’s mission is to get your fingers familiar with these scales, so you have a good ‘playing knowledge’. We won’t bog you down with tons of theory, but we will explain things that need explaining, in an effort to make the info gain some context and remain easy to digest. Our goal today is to have you playing guitar scales easily and with the minimum of confusion. Ready to learn beginner guitar scales? Let’s answer the question "What guitar scales should I learn?" and begin with the most familiar scale of them all, the minor pentatonic…

Minor Pentatonic

Let’s begin here, with the minor pentatonic. Why? Well, it’s very, very simple to get under the fingers, it contains lots of the building blocks you’ll use with other scales, and it’s the first scale that most players tend to learn. As mentioned, each scale has its own ‘sound’ or identity, and either though this one is very simple, you’ll most definitely recognise the sound. So many famous rock riffs and melodies start life on the minor pentatonic, which gets its name from the Greek for five (penté) since there are five notes in the scale.

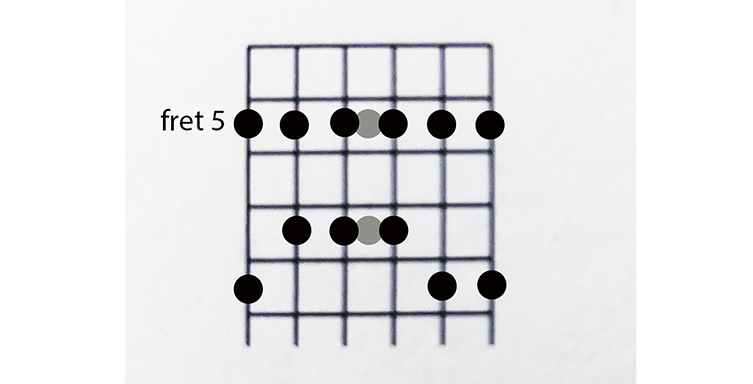

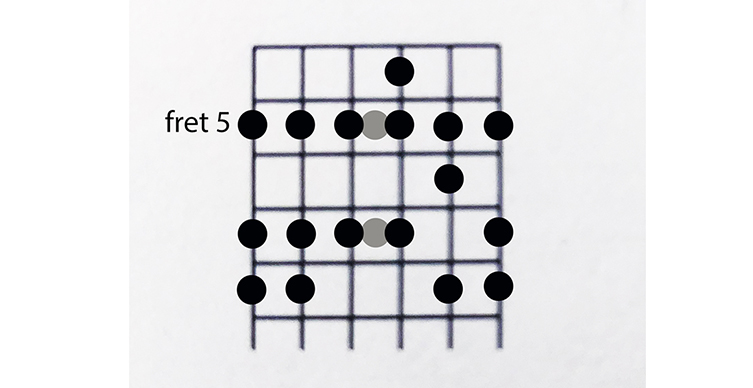

Here it is:

The root note - which is the same note as the scale you’ve chosen to play in - is the logical place to begin any scale. Since all of our examples today are in the key of A, the root of the A minor Pentatonic is A. Here are the notes that make up the scale:

A C D E G and back to A, one octave higher.

Now, that’s the five notes, so why are there 12 notes on our diagram? That’s more a convention relating to how we play the guitar than anything else. Scales repeat themselves (with the same note intervals, of course) all over the guitar neck, in all the available octaves. So, the extra notes we see in the diagram are simply the scale beginning itself again from a higher octave. We tend to stop showing notes after the second note on the top string because it helps the player to see the scale as a ‘box’ on the fingerboard. In reality, the scale continues higher up the fingerboard (and lower down, too) but that’s something for another day. If you can play a scale in one octave, you can play a scale in any octave.

Major Pentatonic

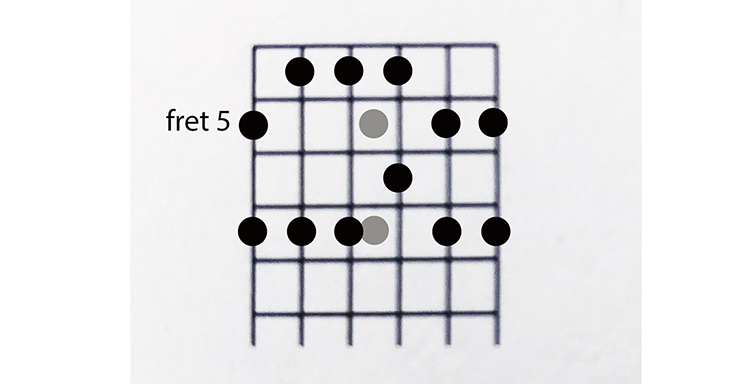

So that was the minor pentatonic, which is used with a minor key. This next version is the major equivalent - the Major Pentatonic - and by learning this one, you'll better understand the differences that occur between major and minor keys within music. We’ll look at this a little further later on, but for now, have a gander at this scale pattern below:

Now, that really sounded nothing like the minor pentatonic, did it? In reality, it only has two different notes in there, but when you play through them all, you get a completely different experience. The actual notes that make up the A major pentatonic are A - B - C# - E - F# and up to the next A.

Played a certain way, the major pentatonic has a really Eastern/Chinese sound, and in fact was the scale found on one of the world’s oldest surviving instruments: a 60,000 year old Neanderthal flute found in Slovenia. So, this scale has been around for as long as we’ve known music!

The reason why these two pentatonic scales sound different will be more obvious when we look at the major and minor scales soon, but first, here’s a scalpel that many, many guitarists learn and then stop their studies…

Blues Scale

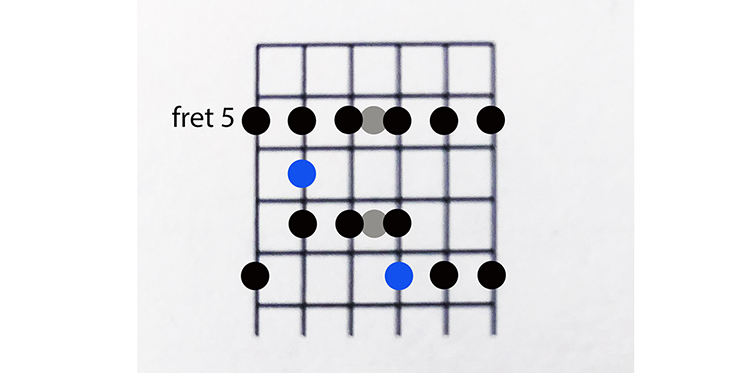

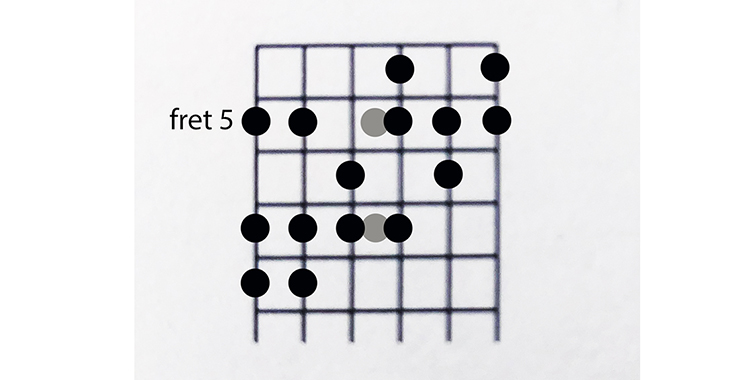

The Blues scale is easily the most used scale on the guitar. It’s also not, strictly speaking, a scale at all, but let’s not bog ourselves down with semantics! We’re here to grab some decent knowledge and apply it to our playing, so for today’s purposes, the blues scale is a proper scale, and here’s what it looks like:

Now, this looks a bit familiar, doesn’t it? That’s because, apart from one extra note, we’ve already learned this one! Yes, the blues scale is simply the minor pentatonic from the start of the article, with an added flattened 5th note. This is depicted above by the blue position dots.

A what? Okay, a tiny bit of theory. A ‘5th’ is simply the 5th note in any given scale, counting from the root. If we played an open A string as our root note, then the 5th in relation to that would be the E note on the 7th fret. We tune our guitars to Standard Tuning - and we talk about that being mainly in ‘4ths’ - which is why the 5th fret is (apart from the B string) the same pitch as the next open string. The ‘4th’ is fret five in this context. The 5th is a tone up, so that’s two frets, to the E at the 7th fret. Make sense? Refer to your guitar when you’re reading that last paragraph and it’ll sink in!

A flattened 5th, therefore, is when you ‘flatten’ that 5th note by one semitone (one frets’ worth). Since we are playing in A, the flattened 5th is a B flat. In times gone by, this interval was known as the diabolis in musica (the devil in music, or the devil’s interval), because of its dark, threatening sound in context with itsit’s key. In terms of guitar playing, we call it the ‘blue’ note, since blues music makes extensive use of its sound.

The blues scale is proper guitar hero stuff, so if you want to start ripping out epic solos, this is the one to learn backwards and inside out. The addition of that one note (notice that it occurs in two places here, because we are covering more than one octave, as discussed before) makes a massive sonic change to the sound really defining the character of the scale. It’s almost a guarantee that all of your favourite guitar players have made good use of this pattern, so get it under your fingers as quickly as you can!

The Major Scale

The major and minor scales are the solid, fundamental building blocks from which all music is built. So far, we’ve looked at some scales which derive from these, but now it’s time to take in the full scale and open up the wonder of the guitar fingerboard.

First up is the major scale, and whilst it’s a little glib to say that the major scale equals happy, it’s also not too far from the truth. There is a positivity to this scale, a sort of musical optimism. Here it is, as ever, shown for the key of A.

The major scale uses seven notes plus the octave note of the root note, making for 8 in total. It’s also known as one of the diatonic scales, but in all honesty, that isn’t too important right now. Getting the intervals right (the spaces between each note in the scale in terms of semitones and tones) is more important than anything, because once you know the intervals, you can pick any note as your starting point and play a major scale since you know which intervals to use. The major scale looks like this, when described as musical intervals, using ‘whole to mean a whole tone (two frets) and half to mean a halftone or semitone (1 fret’s worth of distance between notes):

Root note - whole - whole - half - whole - whole - whole - half.

In guitar fret board terms, you could choose to think about it more like this:

Root note - 2 frets - 2 frets - 1 fret - 2 frets - 2 frets - 2 frets - 1 fret.

Knowledge of this and the next scale underwrite almost everything you do with music, at least in fundamental terms. As you travel further into the world of music and its attendant theory, you’ll return again and again to the major and minor scales. Talking of which, let’s look at the minor scale!

The Minor Scale

The minor scale is actually comprised of three different scales: the natural minor, the harmonic minor and the melodic minor. In realistic terms, when somebody talks about a minor scale, they are almost definitely referring to the natural minor (also known as the Aeolian mode, but don’t worry about that just now!). When the other versions of the scale - the harmonic and the melodic minor scales - are being used or referred to, they will almost certainly be referred to in those terms. So, to speak plainly; we’re calling this scale the minor scale because that’s what the majority of musicians do, but it’s really called the natural minor scale, okay?

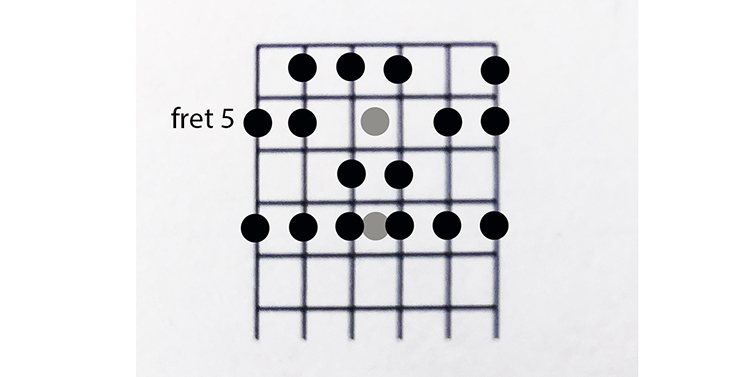

Okay. So, the minor scale is the equivalent to the major in terms of importance, regardless of instrument and genre. Knowing both - and having opinions on how they sound - will be one of the biggest ways in which you can level up as a musician. Knowledge of these scales will lead you forward into things like the Modes, but that’s not for today! For now, please have a look at the A minor scale:

The minor scale is similar in many ways to the major, though with more half tone steps than major. These notes are what give the scale its sadder, more mysterious sound, thought that is of course a matter of personal interpretation. In intervallic terms, here’s what the minor scale boils down to:

Root note - whole - half - whole - whole - half - whole - whole.

In guitar fingerboard terms, it’s like this:

Root - 2 frets - 1 fret - 2 frets - 2 frets - 1 fret - 2 frets - 2 frets.

Playing through both scales should render some pretty obvious differences in the overall sound.

A Harmonic Minor Scale

Our last scale for today has been selected to show you how much you can change the sound and feel of music just by changing up a single note in the scale.

Remember earlier, we added the flattened 5th note to the minor pentatonic and created the blues scale? This time, we are going to take the minor scale we just looked at, and shift just one of the notes. This is known as augmenting, and we’re going to pretty much transform the sound by doing so.

The harmonic minor scale is pretty famous in musical circles because of its undoubtedly exotic sound. Whether the sound of the harmonic minor evokes Spain, the Middle East or somewhere else entirely, it’s most definitely useful for music that has a bit of wanderlust about it.

So, in order to create the harmonic minor scale from the minor scale, we raise the pitch of the 7th note by one semitone, or one fret’s worth. Since our examples are all in the key of A, we want to shift the G note to G#. Here it is as a diagram:

You’ll definitely notice a very particular sound to this scale, right? Lots of music from the Iberian peninsula uses the harmonic minor, particularly flamenco, so it’s a handy trick to be able to pull out when looking to spice up your playing somewhat. Here are the intervals:

Root - whole - half - whole - whole - half - augmented second - half.

In fingerboard terms, it’s like this:

Root - 2 frets - 1 fret - 2 frets - 2 frets - 1 fret - 3 frets - 1 fret.

Building Blocks

We hope you’ve enjoyed this introduction to scales on the guitar. Once you know them, and have them fully trained into your muscle-memory, you’ll be amazed at how often you see them popping up in your favourite music.

This is just the tip of a large and very interesting iceberg, so if you’ve flown through this article, keep up your momentum by discovering some new scales, or indeed some interesting ways to piece together the different octaves. Try different keys, and try beginning from a different octave of a different key and playing the scale down the way (backwards, essentially), since that will unlock cool stuff in your brain, too.

Above all, have fun and enjoy the process! Knowing some guitar scales is infinitely beneficial to you as a player, and it’s not too hard either, if you stick with them for a little while. Good luck!