FENECH GUITARS: guitarguitar talks to Aaron Fenech!

Published on 31 March 2023

This is easily one of the most interesting guitar conversations we’ve ever had.

We recently took delivery of our first order of wonderful Fenech Guitars, and wanted to do a little something to help introduce the brand to you, our customers, as well as familiarise ourselves with them too. Fenech guitars have a beauty, style and sound all of their own, and so it made sense to try to get to the source, if possible, for details. They are a new proposition to us, so this was an exercise in sort of feeling things out. Happily, we managed to secure some time with company founder Aaron Fenech at his Gold Coast, Queensland workshop for a chat. He’d just finished up a long shift (the man gets up absurdly early) and had agreed to hang around to talk to us on Zoom.

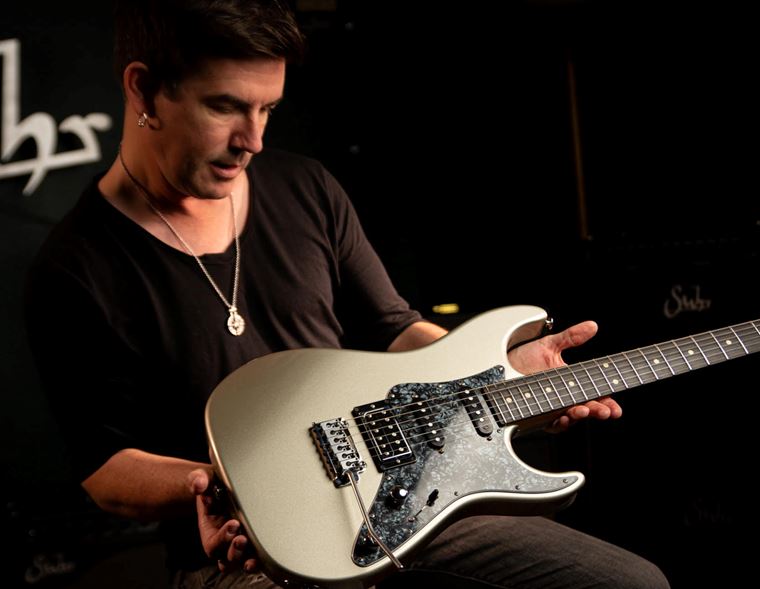

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

What we got from him was one of the most fascinating and detailed conversations about the craft of guitar building that we’ve ever had. Aaron is an extremely interesting guy to start with, and his ability to talk with enthusiasm and authority on every subject relating to guitar making was massively impressive, and very absorbing for us as fellow guitar nuts.

We think you’ll love this conversation too, and it’s all down to Aaron’s quite brilliant, in-depth answers. He’s generous with his knowledge and full of passion for his life’s calling. All of it comes out in this interview, which we’ve transcribed for you below. Fenech guitars are absolutely exceptional, but we’ll mostly let Aaron do the talking now…

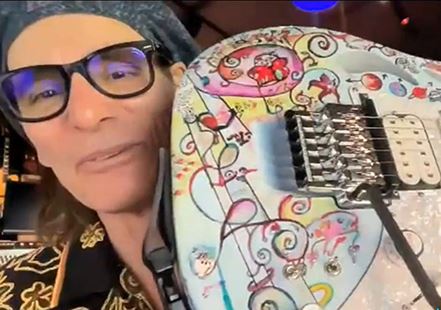

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

Aaron Fenech Interview

Guitarguitar: So, since Fenech are a new brand to guitarguitar, I suppose the most sensible place for us to start is how you got started on your guitar journey? Even before becoming a builder?

Aaron Fenech: Yeah, sure! I finished up with high school and then did an apprenticeship in automotive spray painting, which obviously came in handy later in life! I did that for a number of years, but the funny thing was, I really, really hated doing that apprenticeship! (laughs) Cars are not really my thing. I suppose what it did do was teach me a lot about trade skills, sanding and preparation.

I actually finished that apprenticeship and went and did carpentry, another apprenticeship! That sort of lit the flare in me for working with timber. I’m just one of these people who have a natural flair for seeing something and trying to build it! It’s just one of these things, and it’s quite annoying: I’ll pull things apart and put them back together! Yeah, call it what you will - a little bit of OCD - but it’s what I do!

Then when I was about 24, I went to university and did a science degree. That was quite a broad degree and covered a lot of material science and engineering, a lot to do with the environmental side of things: oceanography, wave mechanics, physics, mathematics. I guess that all embodied into - being a musician and a guitar player - just one day having a light bulb moment: I looked at a guitar and went, ‘How does this thing actually work?’

Again, that curiosity just sort of took over. The first guitar I ever purchased, I actually cut in half just to see what was inside. I mean, this is going back some time ago! Pre-internet. You can just about get an answer to anything now on the internet. There just weren't a lot of guitar makers around, or certainly to my knowledge, at that time.

Then I just started tinkering, really! I had a professional career working in a science field, and at night time I would rush home to the little workshop I’d built, and start experimenting, just repairing and making guitars. I was always quite fascinated with the physical properties involved with a guitar: why do we use spruce tops? Why is that? Has anybody really asked the question, you know? And we have, and there are really sound answers to those aspects but to me it was a matter of: I wanna build it and I wanna test it. I wanna see if I can get to a point where I actually pull levers on a guitar and control tone and structural stability. It’s always a fine line between making something that can perform very well but stay together! That’s really the fine art of guitar making. So, a bit of a mixed background!

GG: Yeah, mixed but it seems that all roads have headed in an inevitable direction for you, with the carpentry and finishing, but also the science element: I’m sure that comes into play with the sort of analytical figuring of things, but - and I might be getting the wrong idea here - but with the environmental science and oceanography, do they play a part in material selection, stability, that type of thing?

AF: It certainly does. Probably the biggest aspect is that, when you’re learning those disciplines, is understanding how waves form in a natural environment. You know, shallow water waves, deep water waves, and there are calculations in both physics and mathematics that help us determine how tsunamis travel across the ocean, and how tides work in a tidal system. Funnily enough, those calculations work in exactly the same way in guitars. A waveform is forming on the top of your guitar, via frequencies. So you’re absolutely right.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

It was actually pretty cool in the early days to make an instrument and place an SM57 microphone in the soundhole then write some little program in Audacity so I could measure it. I’d be thumping the bridge plate and trying to figure out the waveforms.

What the science side of it did for me was be able to actually plug numbers into what I was hearing. Some builders still want to progress down that road: for me, it was about training my ear, to say that I’m hearing a certain thing, the guitar’s performing a certain way. I can see it in analytical terms and in numbers, but it’s what my ear is registering as well.

You’ll see us luthiers tapping on bits of wood and what we’re listening for is frequencies: we’re listening for attack, tone…I’m just sorting through some tops at the moment. A piece of high quality Lutz spruce like this (holds up a beautiful blank slice of timber), what you’re doing when you’re tapping it is checking out the velocity of sound. It’s how fast that sound wave is travelling across that surface. It’s a really good indication of both the physical properties of the material, but also the relationship between the stress and strain.

GG: Ah, so if you give it a tap, because of your science background, you have a sort of opinion on fast vs slow, good vs bad? Do you like a particular response? And what would that response indicate to you?

AF: Absolutely. There’s a question I get asked a lot about my guitars because they sound a certain way. So, listening to a fast response or a slow response, rather than say it’s good or bad, a guitar is very much part art and part science. Art is obviously the way it looks aesthetically; we inlay the top with rosettes, the physical appearance of it because as humans we’re attracted to that probably more so than the tone. But the physical properties that we can listen to, it’s like the guitar is a very very long mathematical equation. Each of those little variables add up to a large number, so sometimes if you’ve got a fast attack top, it might go well with, say, a mahogany back & sides which has a slower tap tone. It’s about mixing the top with the back and thinking about the pairing, and then obviously the size of the instrument, the air volume, how the bracing’s gonna work…there’s a whole range of things that matter. And that’s the beauty of the R&D side of guitar making.

"There's an important lesson as a maker thart you have to learn: not every guitar is for you!"

And so what you guys have bought as the standards in the range, has been a combination of a whoooole lot of R&D that’s gone into defining those shapes and those sizes. The body depths, the way the neck angle comes in: all of it is crucial, and there are a lot of variables in that calculation. You change one, it’s a different result. It’s not necessarily better or worse but it might not be what I’m chasing for my guitars.

In the Workshop

GG: Yeah, that’s really interesting! It’s endemic of a good conversation, that what you’re saying is making me want to ask about five things in response! I wanted to talk about bracing, because bracing is one of those things: whenever we look at a spec sheet for a guitar, people tend to decide whether they want something or not based on stats and specs. It’s useful up to a point.

AF: Yeah.

GG: But something like bracing is a subject that seems hard to say much about, other than ‘it’s X-bracing’, ‘it’s forward-shifted’, whatever else. So, if we rewind to when you mentioned about chopping your first guitar in half - which I think is an amazing visual! - are we talking about taking the top off, essentially?

AF: Yeah, it’s actually on the second level of our workshop and it’s still nailed to the door as a bit of a reminder on how not to build a guitar! I won’t tell you what that guitar is, haha! But yeah, you’re right: with reference to bracing, it is something that with some companies and makers, certainly the largest ones, it becomes a way of marketing the instrument in terms of its performance.

The X brace was obviously something that Martin did a long time ago and most builders have used that, and modified it. But essentially, what we’re doing is, when you have two pieces of spruce like this (refers to the blanks we saw previously) and they’re bookmatched and glued together, that has a certain ‘tapped tone’ to it. But it’s not stiff enough to withstand the strain of the pressure of an acoustic guitar at full pitch. So what the bracing’s trying to do primarily is hold the guitar from collapsing. You put a soundhole in it, and it’s constantly trying to fold itself in half. That’s the first sort of engineering side we need to get right. Then we need to weaken it in a certain way for it to vibrate as freely as possible, but also in a pleasing manner, where we start to get pleasant harmonics and overtones that come from the instrument.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

But each time you see a bracing - and we talk about scalloped or non-scalloped - what we’re actually doing is either choosing to leave mass in the hole, or to subtract that mass and make it more flexible. Again, it’s that constant balance between stress and strain. It’s a beautiful thing because you change one little thing and it changes the entire performance of the guitar. If you move a brace slightly forward, it might open up the guitar, and you know, we’re chasing: there’s directions of movement with a guitar top. You may have heard the term monopole with a guitar? It’s when the guitar top moves up and down, or dipole, when it rocks. What we’re trying to do is make the guitar top as musical as possible but withstand the rigours of decades and generations of playing. That’s the trick: to get the balance right.

GG: That’s some trick to play! So, with your early designs, before you got the point of these current recognisable Fenech guitars - which I think are gorgeous and unique to the point of being recognisably distinctive from other brands - which I think is what every builder wants. Obviously, you follow the conventions of an acoustic guitar but prior to today’s designs, when you started out in building, were there particular instruments that you looked to for certain lessons, that were particularly helpful or influential?

AF: Yeah, without a doubt! I’m made a little different to other makers out there in that I’m not saying that I completely reinvented the wheel. I grew up listening to great American made guitars. Yes, we have other prominent Australian makers and I had their guitars too, in my early twenties, but for me, growing up listening to the Eagles and Neil Young, and all of these great Americana-style bands, there was a signature tone and those guitars realistically were D-18s, D-28s or J-45’s. Really, what you’re hearing is the relationship between spruce & mahogany and spruce & rosewood. Really, they became the benchmark for the sound of an acoustic guitar - rightly or wrongly!

"It takes on average twice as long to make a guitar in my workshop - maybe three times longer - simply because there's some tasks that we don't wanna let go of."

So, in my mind, I was chasing guitars that had that warm, full-bodied sound but putting my own spin on it. This is the beauty of being a guitar maker in the last couple of decades: we do have the benefit of looking at what these other great companies had achieved, what they’ve done really well and what hasn’t worked for them, then building upon that body of knowledge. So, for me it was a great opportunity to say, okay, there’s aspects of those guitars that I really liked, and there were aspects that I wanted to see if I could improve.

We’ve gone as far as being able to achieve a tone of our own but with a familiarity back to those iconic sounding guitars.

GG: Good answer! Which elements did you feel you wanted to try to refine or improve?

AF: For me, most of it was around the way the guitar performed, how it played. As a repairer, looking at a lot of these other guitars, neck angles seemed to be a huge problem. Improving the way that, you know, the aspect that steel string guitars seem to need neck resets all the time. Bridges are lifting. There was a whole range of issues coming through that i was witnessing and I thought, let’s try and fix these issues.

First thing on development was: you may or may not know that on the instruments you have there, we’ve got what’s called an Integrated Transverse System. So, my neck block is connected to a large plate and transverse bar, and a solid piece of lining that goes around the top of the instrument. What that does is prevent the neck from torquing forward and actually causing that fingerboard lift. And it was something that, to me, was a basic engineering principle about stiffening that part of the guitar without sacrificing the maximum amount of area that was left to vibrate. So I tried several different processes in there: some of them completely locked the top up and made the guitar really really tight, and I’m sure you know how that sounds and feels! So the Integrated Transverse System was improvement number one.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

The second one was simply making the guitar more responsive. As factories grow and the need to make more and more guitars happens, it’s sort of inevitable that corners start to be cut, rightly or wrongly, or processes speed up. One of the major differences about the way we build here inside the shop is that each guitar is built individually. We don’t have a pile of spruce tops or mahogany tops or Australian blackwood that we just put through the wide belt sander and everything is sanded the same thickness. No two trees are the same and the physical properties within vary greatly, so we individually stress-test the material that we’re working with, and the tops are flex tested. Some of the tops that you have in stock are maybe 3mm thick, some might be 2.7mm: it really depends on the quality of the spruce that we’re working with. The endgame is to extract the very best out of those individual pieces of material, and effectively, that’s what a custom shop process does. I took the principles from being a ten-guitar-a -year builder and stretched it out to now doing the same process over hundreds. It takes much, much longer to build the instrument but we end up with a fantastic result. We individually optimise the tops, we individually optimise the backs, the internal braces are all carved, they are thickness density tested right down to the thickness of our bridge plate. Some models have a particular species of bridge plate: some may have Indian rosewood, some may have Big Leaf maple. We’re doing that to match what we think are the physical properties that we’re trying to extract, basically, out of the top.

GG: I see, that’s so interesting! I’m gonna come back to that in a second, but to give our readers an insight here - I can see your workshop behind you of course - but you started off just yourself, and now it’s a bigger company. How many builders are employed at Fenech? And are there situations that are better for automation over direct hands-on building?

AF: So, it’s always an interesting conversation when we’re talking about guitars because effectively, it sort of doesn’t matter how much automation there is in a process: guitars really end up being built by hands anyway, because you need to put those parts together. We have very modern equipment here: we have modern CNC’s that carve our necks for us, we’ve got state of the art laser cutters…I’m one of those people where, if there’s a machine that I can afford - that is really really good - if I can’t built it, I’ll certainly buy it.

"All those little steps, we like to get all of those little 0.5%ers, and when you add them up, it's a big number"

There are two sections to the workshop: we’re in the processing section here, where there’s a new machine, a horizontal bandsaw. A very expensive thing (laughs) that basically cuts out a lot of our wood. Rather than buying in the wood and relying on our suppliers to do that process for us, I wanted ot do that in-house. Again, it’s one step closer for me being able to control all those variables.

It takes on average twice as long to make a guitar in my workshop than in, say, another busy, larger company. Maybe three times longer, and that’s simply because there’s some tasks that we don’t wanna let go of. We want our guys to be building the soundboxes using their skilled hands as much as possible. The wood talks to you through that process: as you’re working with certain woods, it wants to move a certain way and that relationship between builder and the instrument, you just end up with a better process. That’s my humble opinion, anyway.

We started out with just myself, then my wife joined the team and she was helping me do bits and pieces. We trained a builder and now we’re up to seven. There’s seven of us building here, full time. All of us build every day, I still do all the processing and cutting of the wood, probably about 90% of the material selection, I still glue every top and every back together: I’m really particular about that process. Instead of having people stand in particular workstations doing one tasks, we’ve chosen to allow everybody to do the process all the way through. We might have one guy particularly fitting necks but the rest of the build is happening right through, basically, with luthiers.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

GG: Amazing! That’s an excellent level of detail for our readers and customers! I love how you prefer to put the tops of yourself, haha! The fact that every staff members is not, as you say, on an assembly line, does that mean that everybody improves in a rounded way? It’s not like somebody is just amazing at putting on bracing but not so good at anything else?

AF: Yeah, you’re right. I wouldn’t profess to say I’m an expert at running a company: I’m learning as well, and I didn’t come from another company and say ‘this is a great way of doing it’. There’s certainly productivity improvements to be had by just having one person do one task, but something I really try to concentrate on here is that, if the individual is doing a process but doesn’t know what comes before or after that process that they’re undertaking, they can’t appreciate the importance of what they’re doing. The guys get really involved in what they’re doing, and they take so much pride in the work: they’re not happy to bring something down and move it onto the next step unless it’s absolutely perfect.

It’s one of the compliments we get when people look inside our guitars: there’s faster ways to glue tops and backs, and most factories will glue them at the same time, but we don’t do it that way. We back the back on first, so that we can clean the instrument. There’s no residual glue left anywhere and our favourite saying here is that we want it to appear like the braces just grew out of the back of the guitar! That requires a very, very neat fit.

So, all of those little steps, all the way through, we like to get all of those little 0.5 percenters, and then when you add them up, it’s a big number.

Timber Talk

GG: Yeah, absolutely. The differences accumulate. We’ve mentioned little bits about timbers and tonewoods. I would like to go into that a bit, partly on account of you being in Australia, which is very very far away from the rest of the world in many respects. Over here and in the US, we’re talking about Spruce, Rosewood, Mahogany. You have different species out there that yourselves and other Australian guitar builders use such as Blackwood and so on. It’s going to have tonal properties that are really similar to other species of wood, and we all grow up hearing those famous Martins and Gibsons you mentioned earlier. Are there other interesting species or combinations - maybe native, maybe not - that have helped Fenech develop that unique look and sound?

AF: Absolutely. We’ve got some amazing timbers in Australia that we can gain access to. Obviously, one of them is Australian Blackwood, which is an acacia and is a very close cousin to Hawaiian Koa. To the untrained eye, it’s almost indistinguishable, you can’t tell! Beautiful midrange presence to it, beautiful treble & bass as well. It’s very stable too, we’ve got very good access to it. It’s a native rainforest tree, and it’s probably the premier tonewood from Australia. It makes a fantastic all-Blackwood guitar, which you at guitarguitar have in stock! I think we built you a really nice jumbo guitar as well?

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

GG: Yes, you did.

AF: I remember cutting that block of wood and it had the most beautiful dark streaks, it was spectacular. Another interesting tree we have here - that is not actually native to Australia - is Camphor Laurel. It was introduced from Asia to Australia in about 1890. The issue with it is, it’s a very prolific grower and it overtakes our natives. It has remarkable figuring, a string pungent smell to it but it’s an amazing tonewood. It has a beautiful mahogany-like tone to it, but probably emphasises a little more bass.

We’ve got a big supply of timbers here that I keep, maybe even some stuff that you’ve not heard of, like Tasmanian Tiger Myrtle, which has pink and black speckling, almost like a leopard. There’s Blackheart Sassafras, so many types of eucalypts here and you can build guitars from them all. There’s lots of lots of special one-off guitars that I’ve built using these amazing timbers. Another great one is Australian Gidgee, which is probably one of the hardest timbers in the world, very difficult to get because no one wants to cut it!

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

Around a decade ago, I was convinced that I was gonna make a guitar out of only Australian tonewoods. That helped me to voice guitars in a certain way: instead of using Sitka spruce tops, we were using things like Australian Bunya Pine, or Celery Top Pine. The challenge with that is, the guitars do sound different.

Coming back to the earlier question about bracing, there’s an important lesson as a maker that you have to learn: not every guitar is for you, and not every guitar is to your liking. It’s that old 80/20 rule: I tend to sit on that 80% of what people are used to hearing and what they’ll like. If you radically change the bracing pattern, it radically changes the sound of an instrument. It’s not that it’s bad, it’s just that it’s quite shocking for someone to hear that, and some people will like it, but it can be a challenge to actually start to sell those instruments when you’re trying to broaden your market.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

For me, it was about extracting the best of what the Australian species had to offer, particularly with the back & side material, and pairing it with a familiar top tone. The heart and soul of an instrument is, without doubt, the soundboard. It’s what drives the instrument, so refining an X brace, moving things around, the shape of the instrument, controlling the air volume a bit different so that the monopole activity of the guitar works the way I wanted it to, helped define and shape our tone.

GG: Brilliant! Such good answers, and so detailed! Thanks for taking the time to explain all this, because that’s the difference between somebody looking at this article for two seconds and somebody stopping and reading it all.

AF: Oh it’s absolutely my pleasure, Ray! I’ll talk about guitars all night if you let me!

The Fenech VT Range

GG: So, all of the guitars we’ve ordered are from the VT range, the Volume and Tone range. I wondered if you could explain why you decided to choose what you did for this particular range?

AF: Yeah, so once upon a time, all I actually built were custom shop guitars. I started to get a reputation locally, I played in rock bands, I was playing acoustically and people would see me playing my guitars. I built guitars for friends and family. I started to get that feedback: could you build me one in Brazilian rosewood? And the guitars started to get very expensive. It was great, and I was building a small amount of really high end expensive guitars, but I’m addicted to guitar making, so it just wasn’t enough for me, I wanted to build lots and lots and lots of them!

I remember the pivotal moment. I was with my kids at a coffee shop and there was a young musician playing there. He knew who I was and he walked up to me and said: ‘I’m desperately saving for one of your guitars but I just can’t quite afford it’. At that time, we were charging a lot of money for a custom guitar. I went away and thought about that. I thought, what I’d really like to do is find a way to broaden the scope and develop a range of instruments that was within the reach of gigging musicians, basically. Maybe not someone’s first guitar, I mean, we’re certainly not the cheapest out there, but certainly someone who has had a few guitars, they are a discerning player, and they are looking for their forever guitar, or something to grow into.

GG: Yeah.

AF: My guitars were always known for having volume and tone so it started the concept of: okay, let’s see what we can fit in. We’ll pack as much as we possibly can into an entry series guitar, and see what prices we can start to manufacture the guitar at. Then each time you step through the range, it isn’t so much about the marketing behind it, it was about trying to put in more than our competitors were doing, because we care about musicians, We didn’t want musicians to come back and say, well, I wanna upgrade the nut’, from a really poor quality nut to a Tusq nut, so, you know, we do that already. Tusq nuts, saddles and pins and really good Japanese machine heads. High quality tonewoods, handmade, all-solid in a great case, with a really good preamp.

So, it was ticking all the boxes, and then idea then was just to step up another 500 dollars: well, what could we include for that? It was a little bit more detail, a little bit more inlay work, and by the time we got to what we call our Professional series, which in Australia is, without doubt one of our highest selling instruments - with the Blackwood - it seems to be the instrument that musicians are aspiring to get to to, or to buy. We’re starting to add things like real Australian Mother-of Pearl block inlays (which we cut here), triple-A tonewoods, and they are genuine AAA woods: I’m going through and selecting the very best material for those guitars.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

So, that’s how it came about, and again, looking at how other companies do it, stepping through the series, but also trying to make it easy for people to understand as well. Each time you step up, you get more. It wasn’t a marketing thing, we wanted to include more value. I was quite particular about all the Fenech wave symbols - that’s my other passion in life, surfing - they’re all inlays. We could’ve taken a cheaper option by putting on a decal or a sticker, but for me it doesn’t speak wonders about our brand, you know? It’s really high quality all the way through. We don’t stack heels on our guitar necks, they are all one-piece mahogany necks, right through the range. It costs more, but we think an instrument of that value should express that quality.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

Plugged-in Tones

GG: Excellent! Amazing. So, one thing that we haven’t touched on that I think is an interesting consideration for an acoustic builder - and indeed for the end user - is pickups. You mentioned putting really good preamps into the guitars. So, anybody can buy a guitar and stick an LR Baggs or whatever into it, but what I wonder is, as a designer and builder, what’s more in line with your goals: do you want the preamp to simply sound really good live, or do you want it to most accurately represent the actual sound of the guitar?

AF: Uh, I think it’s got to be a bit of both, to be honest. There are certainly preamps that we trialled in the early days that sounded really, really natural, but they sounded terrible in a room. And again, certainly in Australia, there’s a real culture that a guitar must have a cutaway and must have a preamp. Obviously, there are other, larger guitar companies here that started this trend, and again, customers want that value inside the instrument.

For me, it was about the preamps being good enough for the sound of our guitars. It was actually one of the biggest challenges in coming to the market: will we come to the market with a preamp installed or will we just ask our dealers to do that as an after sales thing? It bugged me so dearly that I took a trip to China, I met a whole bunch of audio engineers over there, we worked with people in Australia, we went to the US, we went everywhere. One of the issues was, because we effectively hand tune our instruments, the resonant frequencies on our guitar tops are very broad. We’ve got a very, very resonant guitar top and that’s really problematic for lots of off-the-shelf preamps. They’re picking up on lots of excessive frequencies that aren’t typically in overbuilt factory-built guitars.

Again, factories do that for a reason: it’s about having less warranty work come back. The more strength and engineering you can put into a guitar top, the less it’s gonna move over time: the greater it’s going to have a chance of stability. But, they sacrifice a little of the mobility of the top, and therefore your overall tone.

The other thing was, there were preamps that we could find, but they needed to be routed into the side of an instrument, and that was a big no-no for me. I was just like: I don’t wanna go to all the trouble of building these amazing guitars to then go and route this giant hole in the side! Personal preference, but I really like the soundhole aspect of a preamp, and the thing for a musician is that many of the off-the-shoulder preamps just had a volume and tone wheel. The issue we would find is, you bring a tone wheel in, it just overall brings in presence. For an acoustic guitar, we want the kick and the thump, the bass and so for me, it had to have a bass fader, it had to have a treble fader, and more importantly, it had to be warm. We wanted to express the warmth of an acoustic guitar, as opposed to the tinny toppiness you hear from a lot of the piezo-style pickups.

In the end, we worked with Double, a company in Asia, and found a way that one of their systems could be adopted to our guitars, but it just sounds right inside our instruments. Put it inside something else and it might not sound the same way. The other thing was, despite us trying to, I guess, please everybody, chances are we wont. So we wanted the flexibility - we don’t charge extra for a preamp, all of our guitars come with that preamp fitted - but if the customer doesn’t like it, it can be taken out within about two minutes and they can put in whatever they like. If they love an x/y/z pickup, they can place that pickup in.

GG: Amazing! Everybody wins! Now, one of my last questions here, and it may seem frivolous, but I think it’s perhaps more important than it sounds! Given that you’re the designer and chief creator, what’s your own personal favourite model from the Fenech VT range?

AF: Without a doubt, back and sides would be Camphor Laurel. There’s just something…we were talking earlier on about the mathematics, the physics and the velocity: that wood breaks all of those rules but for some reason, when it’s paired with a guitar and the way we build, it just sounds so right. Every time we set up the guitars, both myself and Rob who also sets up the guitars, we just look at each other and we’re astonished, every time! It just has this beautiful warm quality that makes you wanna pick the guitar up and play it. Fundamentally, that’s what we all want! So, the Camphor Laurel, mixed with Spruce, in a grand auditorium or a dreadnought. I love them all dearly, but if I had to choose one, it would be the Camphor Laurel.

(photo: Aaron Fenech, used with permission)

At that point, we nattered on some more about getting photos and so on, just enjoying the conversation! We could've gone longer but as you’ve just learned, it’s a pretty long article already!

It’s clear that Aaron and his team are dedicated to creating the best guitars possible, pushing the overall craft forwards as they do so. We know you’ll be impressed when you try a Fenech guitar at your local guitarguitar, and so we hope we’ve piqued your interest in the brand today. They most certainly deserve it, and so do you.

We’d like to thank Aaron for giving up his precious time to give us such a wonderful conversation.

Click to View our Current range of Fenech Guitars