Is there a living guitarist out there as influential as Joe Satriani? It’s hard to say. Jimmy Page, Slash, Brian May and maybe James Hetfield are the only ones who come to mind. Satch is in the highest podium of the great pantheon of guitar wizards, and every rock player at some point finds himself studying Satriani’s style, his melodic finesse and his wild techniques. It’s a right of passage for all who want to excel on the instrument.

Joe Satriani is such an outrageously good musician, it stops being about speed and technique, and moves into some other zone of expression entirely. Yes, he can most certainly outplay you, me and everybody else, but he’s far more likely to surprise you with an unusual chord or a dramatic change in tone or groove in the middle of a song. Joe’s shred qualifications are well known but as an artist, he’s far more interested in the rest of the musical universe.

This much is obvious upon first listen to his brand new record, The Elephants of Mars. Far more of a communal, collective gathering of instruments than you’d expect from the world’s best-selling instrumental guitarist, Elephants of Mars is a colourful, adventurous trek through a myriad of styles and terrains, full of melodic invention and rhythmic propulsion. Oh, there’s a ton of guitar, for sure, but there’s plenty else besides that, and at times it becomes really quite unpredictable!

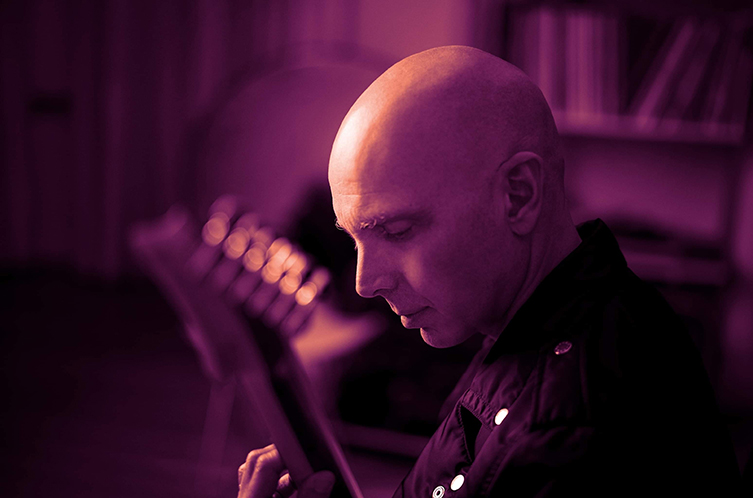

We were lucky to land another audience with the man himself (please head back to our first Joe Satriani interview from two years back if you haven’t read that yet) a month or so back, and found him to be as pleasant and talkative as ever. Joe is excellent at expressing himself and like to have a laugh throughout the interview. He’s a relaxed guy, and frequently scoots around on his studio chair to grab a nearby instrument to refer to or demonstrate a point on.

This new record has been largely recorded remotely, for obvious reasons, and presents something of a departure of the San Francisco-based musician. We’ll let him tell the story himself in this following interview, where we’re learn some somewhat surprising facts about his incredible tone, his thoughts on how a guitar neck influences vibrato, and the story behind the album title…

Joe Satriani Interview

guitarguitar: You know, the last time you and I spoke, it was not long after the first lockdown started in 2020, and here we are: things still aren’t quite back to normal, are they?

Joe Satriani: No, but they’re getting better! I got on a plane and flew to Miami two weekends ago for two art openings. It was a bit weird because we were going to a different state, you know? The US is a big place and every state’s got their own rules. California’s pretty strict, but flying into Miami where people are a lot more relaxed (laughs), everyone looked at me funny, like, ‘who’s that masked California guy?’, you know? We had two really good art exhibitions and that was freaky in itself: it’s just one of those things that I never thought would happen. And the record’s on its way, it’s creeping out there onto the marketplace which really makes us so happy because we’re really proud of the album.

GG: Yeah, yeah, certainly! It’s a great album! It’s always exciting, as a fan of your music, when something new comes around, but this particular one…I’ve been trying to get an angle on it in order to talk to you about it. I’ve been listening to it for the last week or so and it’s beautiful stuff, the songs are great…

JS: Thank you.

GG: Oh, you’re welcome! I wonder if it’s…I’m not gonna say ‘less guitar’, because that’s crazy, it’s a Joe Satriani album! But there’s more space and more instrumentation that kind of takes the lead more often, or brought to the fore more often. Would you agree with that?

JS: Yeah, you know I started out feeling like…well, to start with, it was pretty devastating not to tour Shapeshifting, but I think what was also happening was there was a natural progression where the previous two albums combined with the G3 tour, really made me feel like my reaching back into the classic rock era - that I kinda missed because I was too young - was kinda over. What Happens Next and Shapeshifting were very much like that. You know, working in places and with people from that era and trying to recapture some of that live-in-the-studio vibe. I thought, ‘you know, I think I’ve done that, and now I’m here: I’m painting every day and I’m writing with my Satchtoons partner, and I just wanted to raise my own bar on so many levels. As you pointed out, the sound, the arranging and the compositions. And actually, I just wanted to play better! I just wanted to record myself playing better, and not being forced to leave tracks on an album because that’s all we could do on a Wednesday, because on the Thursday we’d have to move on to the next set of songs.

"It's just a tool. You either bring the right tool box to the gig or you don't! That's the important thing. There is no one guitar that will do everything"

When you go into a studio, everybody knows this, but when you book time in a studio with people, you’re racing against the clock. The money is flying out the window, it's ridiculous! And so you make compromises: you say, ‘that’s good enough’, ‘I wanted to do that but I can’t so I’ll do this instead’, and then you hand in the record because there’s a date (laughs) on your calendar.

This time, we had no clock on the wall and no date on the calendar, and so I couldn’t blame anybody else this time! (laughs) That’s why I reached out to Eric (Caudieux, producer and keys player) and I said, ‘Eric, you have to act as the producer on this one. I just wanna be left alone to really focus on my writing, not feel like I'm forcing myself to make writing compromises, arranging compromises. They all help each other, because you know, when you have a conversation with a partner and you go, ‘Hey, wouldn’t it be great if the whole thing broke down and there was this other thing that I don’t know if anybody could play, but we’ll create a space for it and we’ll spend the next few weeks trying to figure out how to do it.’ That really makes the songs so much more interesting, and that’s what I wanted to get away from. I mean, people know who I am, they’ve heard me play guitar for a long time (laughs), I didn’t want to make a demonstration album. That’s something you do when you’re young; when you’re trying to get your name out there. I’ve done all the demonstrating, I didn’t even want to go near that. Everything to me is about great writing, great arranging, recording and mixing in a way that we never had the luxury to do. This time we did: unfortunately, the pandemic afforded us that luxury.

GG: Yes, of course. Now, there’s a couple of paths I’d like to go down with that, given that you were working remotely… The first one is: how finished were your compositions before the other musicians became involved? In other words, could they send the drums back and then you’d change your mind and they wouldn’t work? And the other path is: did you get any surprises back, like you got an entirely different thing back from what you asked for, but you ended up still loving it? Did anything like that happen?

JS: Uh-huh, just about every song! (laughs) Very perceptive of you. Yeah, I can pull out two really big ones. Night Scene, where Eric and Kenny (Aronoff - legendary drummer) had sent me a bunch of drum takes and there was a section where Kenny was just freaking out in a breakdown area. I heard that and said, ‘Oh my god, Kenny: that’s so crazy! I never even thought that would fit! You do that in the beginning of the songs and I’ll play this funky thing’. So, that became an introduction and it was something that he was just doing, random drum tracks. The demo was very automated sounding: I had done computers and then added the guitar. I didn’t know if Brian could do the bass, I didn’t know really what Ray (Thistlethwayte - keyboards) was gonna come up with: Ray was in Australia and Tasmania so we would contact him every other week or so as he was touring.

So anyway, that was a typical thing, and that’s the kinda thing that would happen in a studio situation where you’re in a room together and somebody plays something good. You go, ‘Oh, we should maximise that little nugget there’.

Another one which was really funny was Sailing the Seas of Ganymede. That song had a very complicated, robust demo that I’d done: I’d put on loops, synths and guitars. I thought the whole song was about as full as you could get it. I had one normal guitar solo there and I thought Ray should do a solo afterwards, and then there’s a drum and bass kind of a thing. So, I sent it off to Ray and he sent it back really fast, but there’s this amazing solo…in the wrong place! I dunno, I probably gave him the wrong instructions but after the first chorus, when the main riff comes in, he starts soloing there, and the funny thing is is that he starts of with one of my typical riffs, and of course I’m thinking ‘Oh my god, that is the greatest keyboard solo I’ve ever heard!’, because first of all, it’s a very weird progression for him to even try soloing over! But he’s so good that he sounds like Coltrane over the top of it, you know? (laughs) But I’m thinking, ‘it’s in the wrong place!’ I then thought, ‘Nooo, now that’s the right place for the solo! Now I’ll just look at the other parts of the song. I’ll just double my guitar solo, rewrite that second half. I came up with this whole other part that I never would've come up with otherwise. I’m not sure if Ray did it on purpose or not (laughs), because I haven’t been in a room with him yet, you know? Once we finally get together, I’ll ask him! We’ll find out if he did it on purpose!

GG: That’s so cool! That particular tune, Sailing the Seas of Ganymede, is one where - I don’t want to say the guitar takes more of a back seat, that wouldn’t be an accurate statement - but there’s certainly sections where the guitar takes a break and the keyboard textures are pushed forward. I wondered, is it simply a case of the guitar having a ‘different job’ on some songs now, that maybe the guitar on a Joe Satriani song in the past wouldn’t have had?

JS: Yeha, a perfect example would be a song I wrote for a movie called Say Anything. Cameron Crowe called me up and asked me to write a song that was all about the character’s kickboxing scene. He’s full of anger and everything and he’s taking it out in the gym. I wrote this song that’s got no keyboards, just two angry, mid-range guitars and this wah-wah guitar mixed really loud, that plays as a singular voice throughout the whole song. That was something I was getting to back then. Instead of overdubbing a verse, multitracking a chorus and then overdubbing different sounding guitars, I thought: what if there was one guy standing in front of the stage and he plays on his wah-wah for the entire song? You don’t hear a break, you know? So anyway, that’s a subtlety!

But yeah, you get a different effect that way. It was a great moment in my budding career to do stuff like that, because you’re really trying to get people to hear your voice, to get used to how you want to speak to them, you know? So you gotta turn it up! As Glyn Johns once said, ‘Joseph, my dear boy, your guitar can never be too loud!’ (laughs) That’s a really bad British accent (it was actually pretty good - Ray), I apologise to Glyn but it sounds very exotic to us Americans. Anyway, so yeah, this time around, when you start to write different songs, you realise, ‘well, I want all of these textures, but if I’m forced to be the guy like in the song One Big Rush, then you just have to play all the time and the overbearing nature of it becomes the quality of the song: people put that song on when they want to get that wah wah guitar clawing at their face the whole, you know? (laughs) I thought, well, I don’t want that!

In Sailing the Seas of Ganymede, I’m trying to create this feeling of one person being on a ship and there are these 200 foot swells of some foreign ocean, and that person doesn’t even know where they are! They’re trying to survive. The main tempo verse in that is really weird: I’m not even sure what key that’s in, I just sort of wrote it on keyboard and then built it with 6 string and 7 string…there’s about 4-6 guitars playing from the very beginning of the song.

GG: Oh really?

JS: But as you pointed out, you don’t really hear it like the One Big Rush wah wah or Summer Song, like, in your face, but it’s part of the whole thing. Then, when the chorus comes in in half time, all of a sudden this big melody comes in and you feel the swaying of the ocean. So, that drama, that cinematic approach is something I was trying to achieve by changing how I’d arrange these songs. Where do I put myself? Sometimes, on a song like Faceless, the guitar is really prominent in the mix: it’s very full sounding, it’s expressing something kind of sad and lonely, but the textures around it are really quite light. The piano that I played at the beginning is, you know, a kid could play that! It was all part of creating a feeling of, like, feeling small in a way.

"I'd written the whole thing on keyboards and I realised that it's got a slightly weird, circus, demented attitude to it"

So, we took extra care with this. Some of the songs, there must be over 100 tracks! The way Eric produces, he spends a lot of time layering things that would take him weeks to explain to you have they got there and how he made them (laughs). I remember days when I wouldn’t hear from Greg (Koller - mixer) because he’d be going crazy trying to mix this enormous track count that Eric would bring into the studio. I mean, what he did with it’s really tremendous. If you heard the demos, you’d be like ‘Wow! That’s a transformation!’

GG: That’s one for the deluxe edition in a few years: the demo disc!

JS: Yeah (laughs), I don’t think it’s a good idea to ever release my demos! That’s only for friends and family members!

GG: Fair enough! I’m gonna come back to Faceless in a second, but you mentioned the drama with the Ganymede song, and I think one notable part of your artistry is that you’ve got such a way of announcing your guitar parts with a really dramatic first note or harmonic. I thought to myself that maybe I’m noticing that more on this record because it’s not having to fight for attention in the mix with another guitar that’s right up behind it. As you were saying, that careful mixing has meant that the dynamic is more pronounced than before and therefore there is more drama. Do you think there’s something there? That your playing has more of an impact when it comes out of the blue more?

JS: Yeah, yeah! I’m so happy you picked up on that because it’s really the way that I hear the music that I listen to all the time, which is vocal rock n roll, I guess. That’s the music that I really still love to listen to. When that vocalist starts to sing, it is the perfect point.

GG: Yeah.

JS: I started to notice - again, this goes back to things that I thought maybe I was guilty of as a young guitar player trying to show off - which is that you don’t see that. Very often, you step all over your perfect intro because you’re really trying to get your toe in the door, you know? I was thinking, if I was 16 years old and could shred, I’d be doing it every day in front of my phone and posting it on Instagram until I got a record deal or something. But I’m not that person and I’m not in that position, so I have no business doing that, you know what I mean?

GG: I do!

JS: Know what I really love though? What I really love is when you hear the vocalist come in at the most perfect moment and they just nail it. I don’t care if it’s Mick Jagger, Tony Bennett or whatever, they have that quality of knowing when to shut up and knowing the perfect time to start telling you the story. So, I really felt that that was a requirement of me, of the highest order, this time around. I wanted to raise the standard of everything on my albums. I’ve got this opportunity now, I’m signed with a new label, it’s kind of a new beginning and I’ve got all this time and there’s no schedule. And there’s nobody in the room, you know? (laughs) I’m not trying to impress, you know, my wife, the producer, the bass player, whatever. No one’s filming for social media. It’s like a release and a relief, and at the same time, you feel the weight, which is: you’re really listening to yourself, and you’re saying, ‘Is that it? Is that all you got?’ (laughs) Because no one’s going ‘Oh, you’re so good!’, you know? Haha! ‘Yeah, I know, let’s just leave it!’ There’s no one saying that, so it’s like, no, this is it! So I really had to lay it down. I guess the criteria I used was different and I think, I hope, that people pick up on that. The note selection and just everything about it is just better than anything that I’ve done before. That’s what I’m hoping!

GG: Oh yeah, even on first listening to Sahara, which was the first track I heard, it is obvious that you’re thinking differently. That extends to vibe, sound, and I expect it will come across. SO, we spoke about Ganymede and the idea of being in this alien ocean. I wondered about just a couple of the other songs, because there’s always some interesting concepts behind your songs. Even the title, The Elephants of Mars: does that have a story?

JS: Yeah, I did come up with a full-on story that I got so excited about, I called my Satchtoons partner and I laid the whole thing on him. He’s the one who does the heavy lifting with the writing. I come up with these concepts and we knock the ideas back and forth. So, I said to him: ‘How about this? It’s in the future, Earthlings have terraformed Mars, unbeknownst to them there is a section of the planet that has produced gigantic sentient elephants. They’re pissed off (laughs) at the humans who’ve come to rape and pillage this beautifully terraformed planet. It just so happens there’s a rock guitar playing - of course - revolutionary colonist there who aligns with these sentient elephants and they start a revolution to wrestle control of the planet away from the evil Earth corporations who just wanna take all the water and minerals outta the planet.

"In the end, for these songs for this album, that little plugin followed, amplified and captured the sound of my fingertip on the string better than anything else"

So, that’s a typical phone call when I call Ned! And I’m trying to slow down enough to get all my thoughts together, but in eight hours we turned around a script that was great: he had character names, the backstories or everybody and he had developed the story to even bigger sizes. So then, I knew right away as that was coming, that this song that had gotten started with this sound that I had made, that to me was the alien elephants, or new elephants or something. As that story crystallised in my head, I realised that should be the title track of the album, and not just because it’s funny and I like to let people know I have a sense of humour, but because it’s one of those umbrella songs. Once you have a song like that, you can fit a lot underneath it: it embraces all kinds of styles. You know, if you call the album Blue Foot Groovy, people would expect lots of Blues and groovy beats everywhere! So, when they’d hear Dance of the Spores, they’d be like, what’s that doing on the album? You know? (laughs)

GG: That’s a good point: Dance of the Spores is one of the ones I wanted to ask about! There’s that really unusual part in the middle, which I didn’t see coming! I’ll refer to it as the ‘fairground choir’ but you know the bit I mean!

JS: (laughing) There’s a funny story about that! Okay, I’ll try to condense it so I don’t waste your time! You know, Eric and I have made lots of albums together. I met him in ‘96 on the G3 live productions: he was doing editing, bringing all the live things together, and making it available to Mike Fraser, who was engineering and producing for us. We did an album together and then he joined the band - he’s a guitar and keyboard player - and then he was involved in I don’t know how many albums now as either a musician, editor or remixer. So, every time I send him these demos for all the songs we’ve had over the decade, I would always put pizzicato strings. There’d always be one or two songs that had a pizzicato part. Over the years, he’d say, ‘Oh man, chill with the pizzicatos! Stop it already! I hate them!’ (laughs) I’d never know why, but I’m sure it had to do with trying to arrange samples and how poorly recorded they are. Meanwhile, I’m just sitting with a keyboard, I don’t really care about it cuz I know I’m gonna overdub it with guitars or whatever. Anyway, it became a joke.

So, I’m preparing that song and I come to this breakdown. I’d written the whole thing on keyboards and I realise that its got a slightly weird, circus, demented attitude to it, but I’m thinking about spored dancing and celebrating, you know? Then I thought, ‘Oh, I know what I’ll do! Just as a joke, I’m gonna do a pizzicato track and then just see, cuz I want him to get annoyed and call me back! ‘Joe, what’s with the pizzicatos? I’ve had enough!’

So I sent it to him, and there’s nothing: I don’t hear anything! I was beginning to wonder: did he get the track? Doesn’t he like it? What’s happening? So then, four days later, I get a little text that says ‘check your inbox’. That’s it. And it’s the song. I’m listening to it and he’s added some keyboard stuff to it. Then I got to that breakdown and of course, he played a joke on me! I was trying to punk him and he just uber-punked me there on that one! And he added - it’s so weird - it’s like the Bulgarian Woman’s chorus and a sort of Mexican trumpet band (laughs), just threw everything on there thinking that would be the joke on my joke. Of course, I loved it and said ‘We’ve got to keep that!’ I just added more guitar on it. Then we thought we should just bring it back in at the end, because it was so weird!

GG: Oh, that is such a good story! It genuinely took me by surprise when I heard it. It’s bold, but it’s really good, it totally works! So, let’s talk guitar tones! That’s definitely something that everybody wants to hear Joe Satriani talk about! I figured I would take two slightly disparate ones from the record and maybe we could talk about how you created each of them, just as a kind of contrast.

JS: Yeah.

GG: The first one is Faceless, which we touched on earlier. It’s a very lyrical, expressive piece, not such a high gain sound, that kind of idea. Then the other one is Pumpin’, perhaps the main sort of solo sound. It’s wild! There’s beautiful fuzz and overtones and stuff. So yeah, how did you go about dialling up the Faceless tone?

JS: Well, the crazy secret is - and you have the benefit of being able to see behind me in this room - I’ve got lots of cool amps. I’ve been very lucky to come across new and old stuff that I’ve used for almost 40 years. But, the weirdest thing about this album is that we started with DI tracks, and like a lot of records I’ve done since 99, we do a lot of DI recording all the time, even if there’s an amp set up. We can re-amp later on. If we want to get away from the drums or we’re waiting for this better amp to arrive or something.

"You can go out and spend $400,000 on a 1959 Les Paul: you will never sound like Clapton on the Beano record!"

So anyway, at my disposal are all the latest plugins, my own AmpliTube ‘Surfing Suite’, all these amps behind me and everything, but what happened was, we wound up always liking the Sansamp plugin. This is the weirdest thing! So, we didn’t really think about it until we started to get towards mixing. We’d listen to the old Marshall reamped, my new Marshall, the EVH, the Wells amp, all the Fender combos. We’d listen to all of the coolest modelling suites that everyone is screaming about, and they were all pretty small. They were all pretty small. We were scratching our heads, saying, how come Sansamp sounds really great? What is it about it? And I think, in the end, for these songs for this album, that little plugin followed and amplified and captured the sound of my fingertip on the string better than anything else.

This kinda made sense to me, because the last couple of albums we did were in really beautiful studios. You know, Skywalker, Sunset Sound. Some really fantastic albums were created there, but I kept walking out of those studios thinking: that was 99% the way I really sound. But why does it sound like something else? That microphone is not hearing the sound that I’m making with my fingers the way my ears are hearing it. Is there something wrong with our technique? Is it just that when you start to use real amps, you have to make all of these compromises with EQ? I haven’t really figured out the explanation for this, but the shocking thing was, at one point Eric and I said: ‘Oh my god, you use the Sansamp for everything! There’s no amp on the album! There’s no modelling guitar on the album. There’s just my guitar going into a Millennia Media mic pre, straight into Pro Tools, going into the Sansamp plugin.

When Greg mixed it, he pulled my performance off and put it through an 1176, just some great vintage gear that John Bryan had at this studio - thank you, John! - and that became the sound of the album. It sounds like a million amps, that’s what’s so crazy about it! The cleanest sounds, to the most dirty sounds are all the same thing, and once in a while I’d have some pedals on the ground, like the Sub ‘n’ Up, or an Octavia pedal, the little Hendrix pedal that Dunlop makes. Nothing exotic, just stuff that you can get in any guitar store. That’s all it was, really! It was how we arranged the thing that you get to hear the full size of the guitar, you know? Like in Blue Foot Groovy, it sounds so vintage but it’s not, it’s just a DI’d guitar with the Sansamp.

GG: No way!

JS: Haha, yeah, I know! I thought, if I knew that years ago…! (laughs) I’ve spent so much money chasing old Marshalls. I mean, I have purchased, refurbished and then sold so many Marshall heads, I just feel like an idiot for having thought that was what was really gonna make a difference.

GG: Joe, that’s actually been really, really validating, because I was thrilled by the guitar sounds on this album. As a guitarist for over 28 years now, I guess I’ve got a tough set of ears to beat! You know, whenever I record with Guitar Rig or whatever, what you’ve said really validates the notion that it doesn’t actually matter when you have the genuine Klon Centaur or not. Really, what’s happening - as you said - between the finger and the string is what’s important, right?

JS: Yes, yeah. It really is. I mean, the classic rock era to me is just really fantastic, I really love it. But they were living in the moment, and that’s the thing that you really can’t reproduce. You can go out, you can spend four hundred thousand dollars on a 1959 Les Paul: you will never sound like Clapton on the Beano record (laughs). It’s just not gonna happen!

GG: Sure.

JS: You know what I mean?

GG: Yeah, yeah! It’s kinda like the guy who buys the perfect hendrix set up with the Univibe, the Fuzzface, the upside-down Strat. It’s like, if Hendrix was still around, he’d probably not have been using that same stuff for the whole fifty years, right?

JS: Haha, yeah, because he used to walk down to Manny’s in Manhattan and buy a brand new Stratocaster! I mean, come on!

GG: Straight off the hanger on the wall!

JS: Yeah, with the big headstock.

GG: Exactly! So, that’s true of your more overtly distorted sounds? All of the gain and stuff - apart from those few pedals you mentioned - is all coming from the Sansamp as well?

JS: Yeah. The thing that’s interesting about it is, I found that by using some other plugins before and after it, you can play with the gain. You can bring up a plugin for an 1176 (famous studio compressor: Ray) and limit your guitar, and then change how it hits the front of the Sansamp. Or you can use the Sansamp preamp control: it’s got very few controls on it but you gotta play with it. I mean, you could sit and play with it forever. You have to know what the band sounds like.

One of the cool things about recording in the studio with a band, like back with the Chickenfoot recordings (Joe’s all-star band with members of Van Halen and the Red Hot Chili Peppers - Ray), we were all in this small room in Sam’s studio, just four feet away from each other, and if you could hear over Chad’s drums (laughs), you’d kinda dial in your amp, you know? But there’s a synergy that happens, because you realise this is how it, that’s how he sounds so this is how I’m gonna fit in. So, when you’re recording piece by piece remotely, you still wanna wait. That’s why we always did so much reamping, because we never knew what the final drums were gonna be like. Once we’d got the final drums, we’d go, ‘Oh, the guitars are too fat! Or the guitar’s too skinny, or too bright or whatever, and you can make adjustments from there.’ The Sansamp plugin is like ‘wow’, I mean, you can make it sound like anything from the cleanest, you know drip-edge Champ or Princeton all the way to a Soldano or something. And like I said, you can put other plugins before, after, or you can make it super clean, like at the beginning of Blue Foot Groovy where it sounds just like a real Strat into a real Fender amp with a mic up real close, but it’s not!

GG: That’s so good!

JS: It’s an Ibanez into a Sansamp plugin!

GG: That’s really interesting because one of the things I really liked - certain guitar moments on this record - are when these harmonics emerge from the note after a while. I was expecting you to be walking around the studio room with the amplifier to get the right feedback note! Would that be more to do with the Sustainiac on the guitar?

JS: Yeah, yeah. I did a lot of playing around where, within one performance, I’d be playing with the Sustainiac on and then turning it off for a few notes and then turning it back on, changing which octaves it’s looking at. Because you can choose which octaves it’s working off of, let's say it’s taking your highest notes and making them even higher, it won’t really respond to low notes. It seems like it’s off when you’re playing lower, and as you move up towards the 10th-12th fret, suddenly every note wants to take off and it goes from fundamental to 5th, something like that. So, you have to kind of learn your gear and your part and go ‘Okay, if that’s gonna happen, then maybe as I move up, I gotta switch which octave it’s going to exploit, you know?

"It really does take a guitar neck about six months until it understands what it's meant to be doing!"

The last song on the album (Desolation) was actually a good example of how I improvised a performance and during it, I was doing a lot of that switching as I was reacting to what I was playing. We had to go in with Pro Tools actually, and mute some of the switch noises because there’s no drums and guitars are so damn noisy when you get gain on them! That’s how I get that effect, when the note takes off and other times it decays. There’s a lot of switching going on.

GG: It’s brilliant, it sounds so wild! I guess there’s a happy medium between a little bit of handling noise or ‘realness’ as it were, but sometimes it’s too much, right?

JS: Yeah, we didn’t clean up everything. That’s the funny thing, when you’re working with a digital interface. You can ‘see’ the noise and after a while, when you’re sitting there editing, you go, ‘Oh, I see another noise! Get rid of it!’ And then you listen back and go, ‘That doesn’t sound like a guy playing a guitar, what is that?’ (laughs)

GG: Totally!

JS: So then you just go ‘fuck that’ and go back to letting the noise be there. It’s like, where is it truly annoying and where is it taking your attention away from a good drum fill or keyboard fill?

GG: That’s a good point!

JS: I think 104th Street, that particular track (E 104th St NYC 1973) that one was a live performance, me on the wah wah pedal. Damn noisy, those things are! I wasn’t even thinking ‘song’ when I recorded that. I sorta had a free moment, and then when I listened back, I was like, ‘Wow, that’s a song!’ Never did that before! And then I had to go back in for the (makes static whooshing sound) and minimise that.

GG: Fair enough! Now, let’s talk guitars for a second. All of this record was recorded with your Ibanez JS models. I guess my main two questions were: I saw a photo of a Black Paisley JS and wondered if that’s something that’s going to be released (Joe reaches to the side and holds it up) Oh, there it is!

JS: Yeah, it should be. This is the prototype. My wife drew these paisleys free hand and then they wound up in these straps, actually (Joe’s signature Planet Waves strap range) that have been out since 2019 in various different colours. Then we wanted to do a guitar, so they sent us a black body and she cut out a bunch of her drawings. We photographed it, we sent them down to the LA custom shop and they went to a guy in LA who does decal work.

It’s basically a 2480? I never get my numbers right! It’s a Muscle Car Black Ibanez JS guitar, 24 frets, Sustainiac, Satchur8 in the bridge. I believe this one will come out, and we’re working on one that I’m not supposed to tell you about! It’s a surprise!

For this record, I used this prototype Paisley guitar, I used a Muscle Car Red one, I used one of my Chrome guitars - I think number 3 - the one I use the most. I used my 7 string, the prototype and the only one I’ve ever had, really. This is on two or three songs. I don’t have the other guitars here: an Ibanez 12-string and a Fender 1966 Electric XII. Those two just sound great together: the Ibanez is very fat, beautifully intonated and the Fender guitar is a piece of crap but it has that vintage sound! (laughs) Very thin and kinda nasally. I should probably re-fret it or something. That’s the problem with vintage guitars: you go to fix ‘em up and they lose value!

GG: Totally! It’s a mean catch-22! Here, Joe: see your main Ibanez guitars? I don’t know if this is a really silly question but are they made by the J Custom guys over in Japan, or are yours made in Los Angeles?

JS: Oh, no they’re the Japanese made ones! The ones I’ve got here have got little pieces of tape on them to remind me which one it is. So this one (Joe grabs a Muscle Car Red JS guitar with a small ‘1’ sticker on the side of the headstock) would’ve been the very first one they sent me where they said, ‘How’s this? Can’t we make these now?’, you know? (laughs)

GG: Oh, cool!

JS: And after we spend a couple of years working on it - this came after the Orange one so everything was designed, we were just trying to nail the colour - I just play them. It really does take a guitar neck about 6 months till it understands what it’s supposed to be doing. It’s kinda nuts that I do that, I really should be playing guitars that are at least a year old, when the necks finally get set, you know? I find it really important to play them in order to understand them, because eventually people are gonna buy them and I wanna know everything about them, so I wind up taking them out on tour. Usually on tour, you see pieces of tape saying I, II and III. I hardly ever take anything else out. I don’t play guitars that are 20 years old or anything like that.

"I just wanted to raise my own bar on so many levels: the sound, the arranging and the composition. And actually, I just wanted to play better!"

It’s really interesting: I was just at Gary Brauer’s (San Francisco guitar tech - Ray) yesterday and we put two guitars on his Plek machine to try to figure out the real subtleties of what I like and what I don’t like. We were talking about necks and how in the first six months, the woods start to dry out and so on until it goes, ‘Okay, this is where I wanna be’. Once it arrives at that, you can go in and sand some of the idiosyncrasies. Then you put it on a Plek machine and it can memorise it. Every subsequent guitar that you put in there, it can say ‘this new guitar is different from the one you really like right here’. We’re talking the smallest increments, but when you’re on stage playing solos and melodies for two hours straight, you feel every teeny little idiosyncrasy of the guitar! (laughs)

GG: Oh yeah.

JS: And you wanna play your best for the audience and so everything’s gotta be as good as possible. It’s funny: Gary has been working on my guitars for, I dunno, forty years of something and we’re still workin’ on it!

GG: Yeah, totally! You’re like - not that I’m speaking for you - but what I understand is that your instruments are modern performance guitars, but you still like the odd slightly more vintage spec, like a little bit of a radius on the fingerboard, for example, and more vintage frets over humongous jumbo frets, don’t you?

JS: Yeah. Although, I mean, this guitar (Joe picks up a white Ibanez JS model with the hand-drawn alien characters), we put this on the Plek machine and it has a bit more of a radius to it. It’s a bit more rolled (at the fingerboard edges), it just so happened. It sounds beautiful, this guitar: really wonderful feeling, super comfortable feeling, and straight as hell, relatively speaking.

And then I brought this one in (the black Paisley finish JS) and again, this is a prototype, so the neck would’ve been made and refretted down at the LA custom shop but all of the components are from Japan and DiMarzio and Sustainiac. This one has got a flatter, more pronounced radius, probably closer to 15” or 16”.

GG: Oh wow!

JS: We use a compound radius, so it feels like a Fender Strat up here (first position) and it transforms into a Les Paul and then something like a Jackson or Charvel, you know? A little 80s tapping monster. But this one,for some reason, was flatter sooner and it just stayed super flat. The cool thing about it is, I do some stuff on the record where I was doing more of that technique and it really did help. It wouldn’t be the guitar that I would pick out to do something super bluesy. There’s an insight that I’ve had that the more radiused the fretboard is, the more the vibrato sounds personal. The flatter the board, the more you can’t tell! So, the flatter the board, the more it homogenises the vibrato.

"If I was 16 years old and could shred, I'd be doing it every day in front of my phone and posting it on Instagram until I got a record deal"

GG: Interesting!

JS: I don’t know if I’m right, but I swear this is what I’ve been noticing for the last 20 years. You get like a Tele or a Strat that’s got a 7.25” radius: hard to play any kind of modern tapping or anything on that, it’s just so unbalanced, but when you vibrato the note: wow do you hear your personality! You can pick out that it’s you. And then you pick up a total metal shredder guitar and you go ‘Wow, I sound just like everybody else!’ and, well, that’s either good or bad (laughs) depending on what your gig is, you know what I mean?

GG: Yeah, haha!

JS: So, I’ve always looked at this super-flat, jumbo fret kinda thing with a little suspicion.

GG: I think you’ve hit on something there, Joe! I think you’ve touched on something! I always thought more about the shape of other elements, but the vibrato and the radius, that’s very interesting!

JS: Yeah. I mean, it’s impossible to get low action on a super-radiused guitar. I mean, the physics of it: you have to raise the action so the strings don’t fret out. So that’s the beauty of the flat fingerboard: you can bend is much as you want and you’ll never fret out, you can have a super-low action and the low strings won’t be too boomy compared to the treble strings where they’re way louder, there’s lots of great things about it. It’s just a tool. Think of every little part as being a bunch of little tools that are part of a tool box, and you either bring the right tool box to the gig or you don’t! (laughs) So, that’s the important thing. There is no one guitar that will do everything.

I love these though. They feel great and they allow me to express myself like no other guitar, so I’m extremely grateful that I get to play these!

GG: Absolutely! Now, I won’t keep you too long Joe, because you’ve been very generous with your time, but I’d love to hear more about the paintings you’ve been making and the exhibitions of your work! I wondered: does your creativity for painting come from the same place as t your creativity for music?

JS: Probably, yeah. I’m not trained as a painter but I did receive training as a musician. I had drum lessons when I was really young, and I learned music theory in high school. I took some lessons from Lennie Tristano (jazz pianist) and then of course I’ve been on stage since I was 14, and that’s where you really learn! With painting, it’s really different. I do it alone, I’ve never been instructed other than my family members who are all artists. That part of it’s a bit different though: if you said to me, ‘Hey, come on over and let’s paint!’ I'd be kinda nervous because I don’t do that! It’s like someone who doesn’t jam, right? (laughs) They just pay in their basement, they don’t play for anybody or with anybody, so it’s kinda like that. I suppose it’s a more personal kind of expression. I mean, I do the art for the straps, and the funny faces on the guitars and picks, merchandise and stuff but it was never for canvases. But I slowly got into the idea of it! Still, when I walked into the gallery last week, I was really shocked: I just never thought someone would hang up some of the weird things that I love to paint! It was also interesting to see: I tried mixing it up with more everyday objects and concepts along with what I really like to do, which is strange disturbing faces. So that was all very interesting, and meeting the patrons and people who bought the artwork, getting to spend time with them, was really exciting. I love that! It was like meeting people out by the tour bus at the end of a show: it’s really a great meeting of fan and artist, a great exchange.

GG: Aw, that’s so great! I’m glad it’s been a success! Now, my final question for you is one of those cheesy ones but I think it’s worth asking and I would love to hear your answer. It’s simply: how does it feel to wake up every morning knowing that you’re one of the most well-loved and celebrated guitar player-artists of all time?

JS: (laughs) I never wake up in the morning thinking that! I don’t feel that at all. No. You know, I woke up this morning and said, ‘Did I sleep?’ Because I can’t remember sleeping, I feel like I’ve been awake the whole time! (laughs) So yeah, I don’t think about that whole guitar thing. Once I start functioning, I start thinking about what I wanna do on the guitar if I’ve got any time in the day, you know, to play!

GG: That’s very humble, Joe. Now, just to wrap it up, the last time we spoke, the tour had been postponed due to the pandemic. Are there tentative plans to go on the road at the moment? Or are you just waiting to see what happens?

JS: Still waiting. Every week we probably have four or five phone calls with our agent and the promoters, all of our partners that we’ve worked with for decades. At this moment, I don’t know what’s happening yet. As soon as we find out, of course, we’ll tell the fans what to expect. I know there will be touring this year: I’m confident that the world is getting a hold of this virus enough where we can safely travel. I mean, that’s the problem for me: we do 9 week tours and live communally in a tour bus. So, it’s not a private plane and everyone has a suite at the Four Seasons! We play places where the dressing rooms are communal as well, so it’s like: the stage is safe, and the audience is safe, but behind, backstage is still a problem. Once we get stopped, what are the restrictions in that particular country or city and it’s so unknown that you could lose everything just trying to play some shows. Sometimes it’s better just to wait, so that’s what we’ve been trying to do, just like most people.

GG: It could be like, a month later and everything’s back to normal and it’s like, ‘If only I had waited, it would’ve been easy!’ You know?

JS:Yeah, yeah.

GG: Before I go, Joe, your comic Crystal Planet: are we ready to have a new issue yet?

JS: Yeah, number 4 is going to the printer I heard, and we just started getting some of my artwork to get worked into the retail version. It’s been online ordering because in the comic book world, basically they don’t stock with retail stores until you’ve had at least four issues. I dunno who made that rule! Now we’ve passed that milestone, we’re preparing new issues that will also go with some of my artwork worked into the covers. They’ll be exclusive for the retail outlets. We’re still on track for the graphic novel later this year, so it's moving forward! It’s very exciting, it’s really great!

At that point, Joe and I veer off to discuss another guitar of his and some modification experiments he’s been working on. It’s one of those situations where we could’ve kept going for another hour, but Joe had a day full of interviews ahead of him and so we had to shelve our guitar geek chat for another time. So it goes!

It’s always a great pleasure and privilege to spend a little time chatting to an obvious master of the craft. His dedication to music and melody remain unwavering on almost 20 albums, and he shows no signs of stopping! My biggest take away from our conversation was that the idea is always the most important thing, followed by the execution. The closer he gets to that initial inspirational image or narrative, the happier he seems to be with the music that results from it. That was my take, anyway!

Since our conversation, Joe’s team have rescheduled the tour for April-June 2023, so head over to the official Joe Satriani website for more info on that and links for tickets. The Elephants of Mars is released on April 8th on all platforms and is a quite wonderful listen.

We’d like to thank Joe for once again being a most excellent interviewee, and to Peter Noble for putting us in touch. Thanks, as ever, go sincerely to you for reading this interview! We hope you enjoyed it, and there will be many more in the future. If you liked this one, please head over to our guitarguitar interviews page, where you’ll find interviews with Steve Vai, Joe Bonamassa, Nili Brosh, Ian Thornley and many, many more!