The guitarguitar Interview: Tomb Raider composer Nathan McCree

Published on 06 December 2019

Standing silently in awe on top of a colossal underground Egyptian Temple...

Dodging a literal Sword of Damocles in St Francis' Folly, Greece...

Finding Qualopc's Tomb in the underground village of Vilcabamba, Peru...

Beating Pierre Dupont and Natla Technologies to learn the secret of Atlantis, and it's eventual fate...

If any of those words resonate you, you will be just one of the millions who have been captivated by the mystery and adventure of Tomb Raider. One of the most successful game franschises in existence, the Tomb Raider series, and indeed its charismatic 'female-Indy' star Lara Croft, are permanently inscribed in the imaginations of millions of gamers throughout the world. If you are the type to enjoy a good factoid, here's one for you: Lara Croft was awarded a Guiness Word Record for being the "most successful human video game heroine" on the planet. Spiky blue hedgehogs and Italian plumbers are, naturally, not included, but still!

First released in 1996, Tomb Raider arrived at a time that coincided with a technological upswing in console hardware. This explosion of technology for both console and PC gaming meant that games could now be bigger, more ambitious, more detailed....and have much better quality music. Few games understood this as well as Core Design's Tomb Raider. Lead designer Toby Gard wanted to create an ambitious 3D adventure in the style of Indiana Jones, but for a modern audience. Steeped in mystery, adorned with esoteric Egyptian imagery and bringing an unheard-of level of realism and immersion to the game world, Tomb Raider was the very definition of 'game-changer'.

One of the most unforgettable aspects to the game was the soundtrack. Valuing space and atmosphere over adrenaline and noise, Tomb Raider's elegant and beautiful score gave a sense of awe and scale to the adventure. Silence and timing were priorities. For example, most gamers remember the surprise 'T-Rex' moment a few levels in, but just as many recall the silent gasps they made when, after minutes of eery silence whilst wandering into a dark cavern, a colossal Sphinx face slowly appears, gradually revealed from within the subterranean darkness, accompanied by the sounds of Gregorian chanting and solo violin. The music swells into a fuller orchestral piece whilst the in-game camera pans out and takes a swoop around the vista, swamping you in scale and grandeur.

It's breathtaking stuff, and the man responsible for the musical side of things is Nathan McCree. Writing, recording and producing the entire score by himself, McCree went on to score the following two Tomb Raider sequels for Core, defining the epic franchise's sound more than any other composer. His music has had a long life, being listened to by fans ever since. In fact, it is still so appreciated by both the gaming and the classical music communities, that a recent kickstarter campaign to record an orchestral album of the music was a resounding success!

Tomb Raider then, as we know, then became three movies, almost twenty games (including a spectacular recent reboot trilogy), and much more. Back in the late 90s, Lara's likeness was used to sell Lucozade, she 'modelled' on the front cover of The Face magazine, and became a bona fide cultural phenomenon, quite outside the historic thrills of the games themselves. It is amazing to consider how big the tidal wave grew, considering how inauspicious its genesis was.

In this rare and in-depth interview with Nathan, we get a chance to learn about the genesis of Tomb Raider's music, the equipment that was used to make it, the legacy of such influential work, and the recording of the Tomb Raider Suite in Abbey Road studios by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra! It has been quite a journey for both game, music and composer. Game music is acknowledged today is a relevant and legitimate art form outside of the games themselves, but that wasn't the case in the 90s, certainly not in the West. Nathan's Tomb Raider score did much to move that set of opinions in the correct direction.

Though we understand that there is nary a hint of a guitar anywhere near this music, the value of learning more about the methodology and equipment of a professional composer is something we think would be of great interest to a large number of you. Since most of us record music on our computers, and most of us like more than just guitar music, we feel that this is a fantastic opportunity to learn and gain insight from someone with a great deal of unique industry experience!

Through a series of emails, Nathan and I had a very interesting and satisfying conversation about all things Tomb Raider, starting in the mid 90s and ending up in the near future! We are very excited to bring you this comprehensive conversation! Here it is, along with some excellent behind-the-scenes photos from many aspects of the story throughout the years.

Guitarguitar: Nathan, thank you so much for agreeing to chat with us! Tomb Raider is a significant part of contemporary culture in many ways and you were there right at the very beginning. Before we go back to the beginning, how does it feel to be a part of something so celebrated?

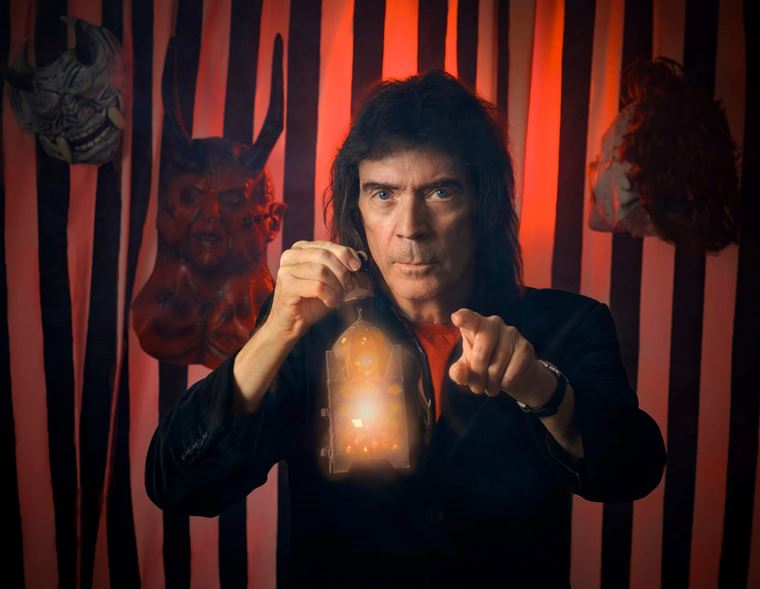

Nathan McCree, Tomb Raider composer. (Photo: Michal Odehnal)

Nathan McCree: Hi Ray, you’re welcome, thank you for the invitation. Well of course I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to be a part of such an amazing project and now it’s really amazing that it has continued for over 20 years and that the fans of the franchise are still talking about and listening to my music. So it does feel great. I am honoured that the music still has so much support from the Tomb Raider community.

GG: Tomb Raider was released in 1996. Did you have any inkling of how special the whole project was going to turn out or was it just another fun, interesting job for you?

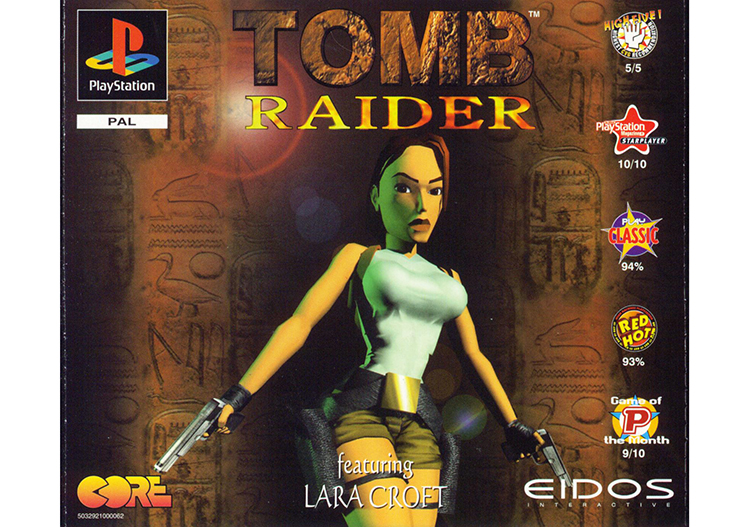

Tomb Raider original Playstation front cover

NM: For me, it was really just another job. I don’t think any of us working on the project really had any idea just how big it was going to be. We knew we had something unique, and for me, from a musical standpoint, it was an opportunity to try something which hadn’t been done before in the games industry. I took a gamble, and from what I can gather, it worked!

GG: How far along were the team in designing the game when you came onboard? Did their design work influence your music?

Lara Croft Concept design. (Art by Toby Gard)

NM: For the first game, I think they were about 4 weeks away from completion by the time I started my work. There was stuff for me to look at but time was short, so I really drew my inspiration from the character of Lara Croft. I talked mostly to Toby Gard about the style of music and what kind of cues would be useful for including in the game.

GG: What kind of inspiration did you make use of when scoring Tomb Raider?

NM: The script for the video sequences played quite a large part in the design of the music. Ultimately I was trying to create something similar to a movie score, but for a game. So I drew from my knowledge of movie soundtracks and also from my musical upbringing, which was largely fed by my Father’s obsession with classical and choral music.

GG: What was your writing process for themes and cues?

NM: Most of the time, and this is still true today, I start with some quaver or semiquaver pattern, usually played on some percussive instrument (like a harp, piano, cymbalon, rhodes etc), which alternates between my two hands, each hand playing a single note randomly from one of the five fingers, and I keep changing the order of fingers and/or notes until I find a pattern that is repeatable and which sounds interesting for me. That is usually the seed of my track. The rest of the accompaniment grows from that, gradually adding more and more instruments until I have a small orchestra playing. Then I start thinking about a melody and possible chord progressions – all the time incorporating the seed pattern as it undergoes slight variations to accommodate whatever chord changes I need for the melody.

GG: When mixing, do you test your music on a number of different studio monitors?

NM: Ideally yes, but sometimes there is so little time, I have to go with the mix I have at the time. Having said that, I write and mix at the same time, so it’s usually had plenty of attention over the course of about 3 days.

GG: The original Tomb Raider makes great use of darkness and isolation in constructing its unique atmosphere. Was this something you wanted to preserve and enhance with your composing?

NM: The darkness and isolation was influenced by the character of Lara Croft, but also it came about due to the time constraints of the project. There really wasn’t much time to fill it full of audio detail. So invariably the atmosphere and musical content was sparse and minimal. As it turned out, this was actually quite advantageous as it gave the player sonic space to think – something which is critical for solving puzzles.

GG: Tomb Raider is set is various exotic locales, as are its sequels. Did location play a part in your compositional style?

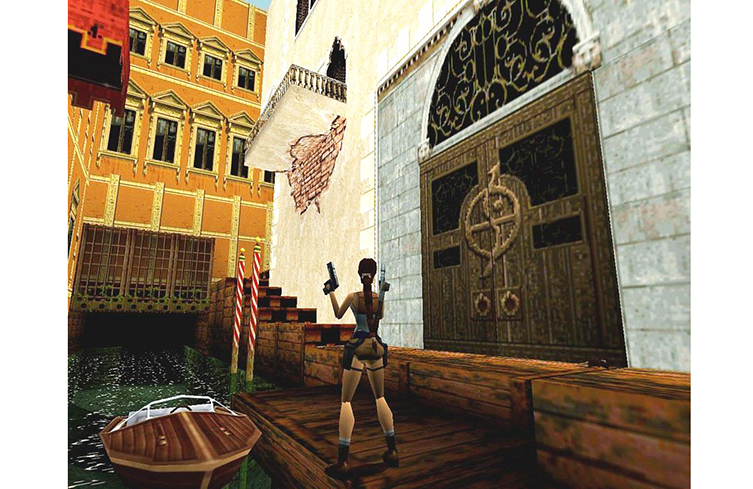

'Venice' Level from Tomb Raider II

NM: Yes of course. In Monastery from Tomb Raider, we have the Gregorian chanting; in Venice from Tomb Raider 2 we have the baroque Venetian strings and harpsichord; in Tibetan Foothills from Tomb Raider 2 we have the Tibetan style drumming; in Something Spooky In That Jungle from Tomb Raider 3 we have the sitar and tabla taking the lead, accompanied by a full orchestra; and there are more examples.

GG: Much of what is regarded as ground-breaking with the Tomb Raider score was your decision to make quieter musical cues than dealt in awe and wonder rather than noise and bombast. This proved to be quite a bold move on your part, compared to how videogames were generally scored: was this simply what the game called for? Was this how you always envisioned the music?

Lara Croft, Tomb Raider II-era

NM: Yes this is how I wanted it. I had been getting fed up of the predictable, fast-paced, bombastic, action music that other games titles had been producing, and I had a thought – if gamers like movies, which have plenty of emotional musical content in them, why wouldn’t they like that in games? I had been looking for the right game, the right opportunity to test my theory, and when Tomb Raider came along, I thought, this is it! - Here was a woman, a beautiful woman; an explorer who was classy, educated, sexy, witty, dangerous and alone. It was perfect.

GG: In the same vein, lots of the instruments used in the score are either orchestral in nature or exotic: how much of a challenge was that with mid-90s technology? You make incredible use of choirs too.

NM: Thank you. The industry had just 2 years previous, made the huge leap from chip-based consoles to CD-based consoles and for us as musicians that was a real game changer. It meant we could use the latest synthesizers (and just about as many of them as we liked) which were very capable of making great orchestral sounds (amongst many other weird and wonderful effects). We didn’t have sample banks then, but many of the synth manufacturers were making sound expansion boards which provided hundreds of specially crafted instruments for all sorts of genres. I was particularly interested in replicating a full orchestra so I had my 2 x Roland synths expanded with the Orchestral Boards 1 & amp; 2 in each machine which gave me pretty much every kind of instrument and ensemble you find in today’s orchestras and also a World Board in each, which gave me hundreds of unique instruments from around the world.

The challenge was getting the synth sounds to sound like it was being played by a real person. For example, with an oboe, you have to remember that this is a woodwind instrument which is normally played by someone blowing into the instrument. You have to remember to give them space to breathe! As another example, a piano has a larger dynamic range, meaning it can sound very quiet all the way up to very loud. So you have to pay particular attention to the velocities of each note, otherwise it just doesn’t sound real. It just sounds like a machine hammering all the notes with exactly the same force, something which is practically impossible to do as a human. String instruments also need detailed attention on the dynamics of each note. The instrument can make a different sound and dynamic depending on whether the player is making a down bow or and up bow movement. This is something which I needed program into my compositions to get the strings sounding real. So across all the instruments in the orchestra, there was a lot of detailed programming to do. That was the biggest challenge.

GG: In fact, just what was your setup for producing game music back then? And did you encounter problems with the limitations of hardware back then?

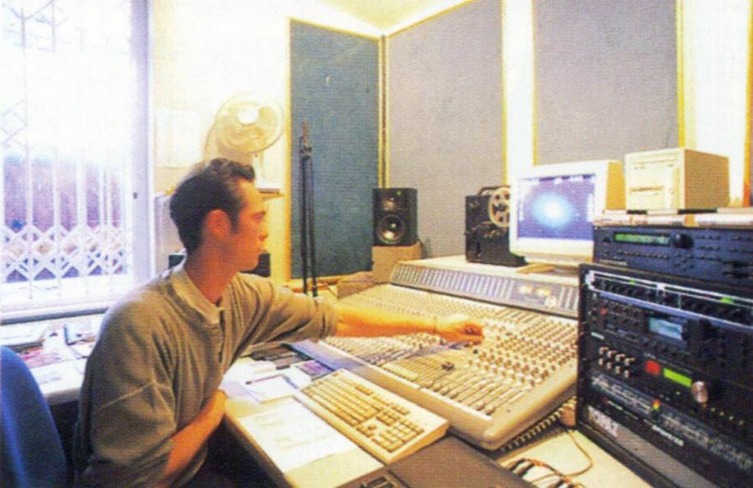

Nathan's studio at Core Design in 1997

NM: I was running Cubase on a Windows PC. I had a multi-port MIDI interface which allowed me to communicate with multiple external devices. For synthesizers I had a Roland JV90, and a Roland JV1080 which is the rack version of the JV90. Both of these were equipped with the Orchestral 1 & 2 Expansion Boards and the World Expansion Board. I also had an Ensoniq SQ1-Plus but I was using it less and less as I progressed with my orchestral scores – it wasn’t so good at producing real orchestral instrument sounds. I had a few other bits and pieces, an Ensoniq multi-effects rack and a Focusrite compressor, and that was about it.

The main limitation I had was note-polyphony. Something I am still constrained with to this day. I had 64-note polyphony on each of the Roland machines and I would, and still do, constantly hit the limit. But it’s actually a good thing, because it stops you adding more and more stuff to your mix (something which is very tempting to do when things are not sounding right) which often ends in disaster. One limitation in the hardware which was quite annoying was recording and editing the final mix. PCs were not as fast as they are today. Once I had recorded a track onto the hard drive, if I wanted to trim the start of the track, or apply a short fade in (which was often the case) it would take as long as it took to play the whole track to make that single edit, something which is almost instantaneous on today’s computers. So that slowed things up a little. Now we have many more tools available to us for manipulating audio tracks once they’ve been recorded, which opens up almost limitless possibilities for what we can do. And much of this can be done real-time so it’s a whole new ball game now compared to how it was back in the early 90s.

GG: The 90s seemed to be a cultural hotbed for games music that has had a long life outside of the game itself: I’m thinking of Tomb Raider, Final Fantasy VII and Silent Hill amongst many others. Was this a classic time for game music or is that just nostalgic hindsight on my part?

NM: I think in some ways it was a classic time. Many of the games composers at the time had previously been working in the industry writing chip music, where ‘tunes’ were all the rage. When the CD consoles came out, I think many of the chip-based game composers continued writing ‘tunes’ into the mid and late 90s. As the industry moved forward however, many of the ‘new kids on the block’ were writing music beds, Holywood style movie beds, which didn’t really have a melody, so there wasn’t so much content to get a grip on melody wise moving into the 00s. I think the importance of melody is understood by some composers and developers, but also I think that melody is often sacrificed when budget and time constraints are tight, and that’s not a wise move because good music is often the thing that can really sell a product.

GG: How does your composing style differ when working on games as opposed to working outside games?

NM: I wouldn’t say the difference is between working on games or working outside games, it’s more a case of working to a tight budget or not. If the budget and time is there, then I can pay more attention to detail, and the end result will contain more interest. If the budget or time is tight, then my writing style will be more minimalist (there may not be enough time to write for 65 instruments, so you write for 20 or 15 for example).

GG: Were you classically trained as a musician or self-taught?

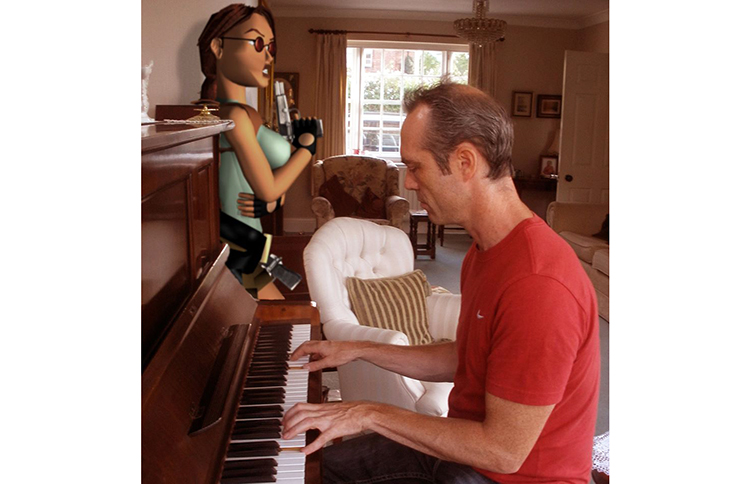

Nathan Playing Piano (Photo: Hana McCree)

NM: A bit of both really. I sang in Church Choirs from the age of 6 until I was 18. So I learned a lot about how to sing and how to sight read music. It also taught me a great deal about 4 part harmony and how that was constructed. When I was 10 I started to learn the piano. I reached and passed grade 7 by the time I was 18. I had a total of 6 piano teachers during that time, so I received a diverse set of playing styles, and that taught me a lot about the instrument and about musical expression in general.

I also studied music at school at ‘O’ and ‘A’ level, specialising in composition. It was the only thing I really wanted to do. When I was 19 I went to University to a study a degree in Software Engineering. I stopped studying music, and focused on composing music in my spare time, which ended up being so much spare time, I barely passed my degree. Fortunately I did, as it helped me get my first job as a computer programmer with the UK games developer Core Design, where I later went on to write the music for Tomb Raider.

GG: As a game composer, how has the industry changed over the past two decades?

NM: So I have been in the industry for 26 years now. The biggest change for us composers was in 1994 when the CD-based consoles arrived enabling us to record anything we wanted and stick it in the games. Over the last 20 years though there has been a steady progression of game engine and audio engine software that has enabled the development of really massive games with huge development teams. I have worked as Audio Director on a few big games, and it really is a different ball game. I’ve had audio teams as big as 8 people, with each engineer being responsible for a particular category of sound. For example, one guy doing just weapons, another, footsteps, another, impacts etc. With some games requiring over 30,000 sounds it really is a monster of a task. But apart from the sheer size of the projects increasing, there has been an increase in console CPU power and speed which means we have been able to apply more and more real-time effects. This enables us to simulate real- world sound with closer accuracy. In general, I think the skills required for sound design are much the same, but the skills required for implementation have increased exponentially. Now we are not just looking for sound designers, but sound designers who have experience implementing with particular game/sound engines, Unreal, FMOD, Wwise etc.

GG: Tomb Raider’s legacy is such that you’ve been able to re-approach the original score for Tomb Raiders I-III and recreate them with a full orchestra and choir (the Royal Philharmonic, no less!): how does that feel on a personal level?

NM: It’s something I’ve wanted to do since as far back as 1997. I remember shortly after the release of Tomb Raider, I had a call from Decca records who wanted to release the soundtrack to Tomb Raider as an orchestral album. Unfortunately, when I mentioned this to my boss at Core Design he said he wasn’t interested. My guess is he was making so much money from the sale of the games that any profit from a soundtrack album just didn’t compare. It was very frustrating for me from a career standpoint. Here was one of the most prestigious classical record companies wanting to record and release my music, but the people who owned my music couldn’t be bothered to just say yes! It was then that I realised I had to leave full-time employment and go freelance. At least then I would have the chance to hold on to the rights in my music. The idea for the album however had been planted in my brain and from then on, I was determined to make it happen.

GG: The Tomb Raider Suite, as the project is known, was recorded at Abbey Road Studios. Was that a magical experience?

Nathan in Studio One at Abbey Road (photo: Dan Millidge)

NM: Indeed it was. Abbey Road Studios is renowned as one of the best recording studios in England, if not, the best, so it was a real honour to have had the opportunity to record there. Just walking down the corridors and seeing all the photographs on the walls is an experience in itself, not to mention sitting in very same seats as all of those people in the studio restaurant. Of course the studios and live rooms are second to none and the people there were just great; a hundred percent professional and a lovely bunch of people. I met some great people there and made some new friends. It really was a privilege to be there, and I have my Kickstarter backers to thank for that.

GG: This seems like a trite question, but I’d still love to hear your answer: what does a live orchestra and choir give to your compositions that software cannot?

Robert Ziegler conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra during the recording of the Tomb Raider Suite at Abbey Road Studios (Photo: Dan Millidge)

NM: Live musicians bring a level of expression and variation which is practically impossible to programme. The way each phrase is played by each section of the orchestra is never the same twice. Each musician brings their own unique expression to the performance. The conductor adds his own expression too by moving the orchestra faster and slower, louder or quieter, phrase by phrase to emphasise the harmonic structure of the piece. The whole orchestra moves together (directed by the conductor) and this is unique for every performance. It never plays the same way twice. The fascinating thing is that the recording we made at Abbey Road cannot ever be repeated. The recording is unique, and that is what makes it so special.

GG: The whole project was funded via an enormously successful Kickstarter campaign. How was that in terms of managing the whole thing? Were you surprised by the response?

NM: To be honest with you, we had been delaying the launch because we weren’t ready, but time was running out and we had to get moving. So we launched with a goal of £160,000 but we were ill prepared and although the campaign got off to a flying start with 30% funding in just 3 days, the next 10 days were decisively flat and our projection curve was set to fail. So we held some critical marketing meetings and restructured our plan. We put it into action and to my delight our funding projection curve began to climb. With more than 48 hours still left on the clock we hit our goal and went on to raise a further £30,000. It was one of the most nail-biting and stressful months I have had in my life.

Was I surprised by the response? Yes. When we first set out planning the Kickstarter Campaign, our budget was around £65,000. At that point I thought, wow, this is a big ask. But as we delved deeper into the planning, the costs just went up and up and up. In the end when we pressed the launch button we were asking for £160,000. I honestly thought we would never make it. I didn’t think we would get £60,000. So to smash our final goal by a further £30,000 was truly remarkable. When the campaign finished, I am not ashamed to say that I shed a few tears in utter joy at the fan’s response. The dream had come to life.

GG: In your opinion, is Kickstarter a viable business model for musicians for now and in the future?

NM: I am not so sure about this. The Tomb Raider project is a phenomenon and I don’t think it can be taken as an example for other projects. And I think an all-or-nothing style crowd- funding campaign isn’t necessarily the right approach for musicians. I think the Patreon style of crowd-funding is better and a less risky solution.

GG: There were some very inspired perks for backers of the project too, including black tie events across the world with ‘real’ Lara Croft models making appearances! Could you tell us about those?

String Fusion playing the Tomb Raider Suite at the Composer Buffet Reception - The Old Palace, Hatfield House (Photo: Mike Riley)

NM: Sure! So we planned two Composer Buffet Reception album launch parties. One at Hatfield House just outside London, UK and one at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, U.S.A.

The Old Palace, Hatfield House (Photo: Mike Riley)

We held the Hatfield House reception on 14 th April 2018. Entrance to the Old Palace was via the Main Gate of Hatfield House, where upon a red-carpet arrival the guests received their welcome glass of champagne, served by none other than Winston himself! (Winston is Lara's long-suffering butler in the games - Ray)

Winston with guests at the Composer Buffet Reception, Hatfield House (Photo: Mike Riley)

Unique string arrangements of a selection of tracks from The Tomb Raider Suite were performed live exclusively at this event by the all female octet, String Infusion.

String Fusion at the Composer Buffet Reception, Hatfield House (photo: Mike Riley)

Guests were able to enjoy a delicious buffet and free drinks all evening while they listened to the UK Premiere Public Performance of The Tomb Raider Suite album. There were big-screen projections of Tomb Raider 1, 2 & 3 we showcased exclusive behind the scenes footage of The Making of The Tomb Raider Suite documentary including scenes from the Abbey Road Recording Sessions. All guests received a unique gift as a memento of this very special evening.

We are still to hold the San Francisco Composer Buffet Reception, and that is the next thing that myself and my team will be focusing on.

String Fusion with Nathan, Hatfield House (Photo: Mike Riley)

GG: Tomb Raider was enormously successful and has been made into films, comics, rebooted into a new series of games and so on. Do you feel that it is time for game composers to be celebrated as much as film composers in terms of cultural recognition?

NM: Yes of course, and I have been saying this for years. The Japanese have been celebrating games composers for the last 40 years, and their game composer soundtrack revenues are bigger than their film and music industry revenues put together. Thankfully things are beginning to change over here and we now have respected award ceremonies celebrating games music and the composers, but I think there is still a long way to go. Certainly in terms of copyright ownership, royalty payments and recognition, the games composer is still the black sheep of the musician family.

GG: Speaking of which, you have also performed the Suite live on several special occasions with a live orchestra. How was the live experience for you? Is this something you want to do more of? And do you take part in the playing?

Front of venue, Hammersmith Apollo, 18th December 2016 (Photo: Stephanie Pettigrew)

NM: The live concerts are certainly the most exciting part of the whole project. It’s such an adrenalin ride getting everything together at the rehearsal just hours before the actual show. It always amazes me to watch a hundred or so human beings come together for one purpose, and how their professionalism shines through to produce such an amazing experience in just a few hours. It really is quite an incredible thing to see. And when you hear them all play together, it completely blows you away, not to mention the fact they are playing music which I composed. I have to pinch myself each time that it is really happening!

The Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra performing the Tomb Raider Suite at the Apollo, 18th December 2016 (Photo: Stephanie Pettigrew)

I definitely want to do more of it, and it is certainly a part of our long term plans for the music. I want to take the Tomb Raider Suite around the world, and that’s what I’m going to do. And no, I don’t do any of the playing. I am there as an advisor, and I usually get up on stage at the end to say some thanks before heading off to the VIP lounge for the Meet & Greet signing session.

Nathan on stage at the Apollo, 18th December 2016 (Photo: Stephanie Pettigrew)

GG: Do you have a personal favourite piece of music that you’ve composed?

NM: I think from The Tomb Raider Suite, I would probably say In The Blood. For me, it captures the true spirit of Lara Croft. It was a totally new piece which I wrote for the Suite so it doesn’t feature in the original games, but I tried really hard to keep it in the same style as I wrote for the original music twenty years earlier. I think I did a good job, as some people have said it was their favourite piece of music from the original games!

GG: These days, what is your composing setup in terms of hardware and software?

Nathan's Programming Suite (Photo: Michal Odehnal)

NM: To be perfectly honest it hasn’t really changed in twenty years. In 1998 I bought a load of studio gear when I first went freelance. I bought a new Mackie mixing console, a Roland JV1080 (Expanded with the two Orchestral boards and a World board), an Akai sampler, a Focusrite compressor, a Rhode microphone and of course my PC running Cubase. The only thing I have added to that in twenty years is another Roland JV1080 (Expanded). I still use this kit to this day, in fact less of it. I have abandoned the Akai sampler in favour of my PC, but I don’t use orchestral sample libraries. All the orchestral sounds come from the 2 x JV1080s. I guess you could call me old school, but I know my kit and I know how to make it sound good.

GG: Does the technology make your job easier? Things sound perhaps more realistic, but does that make them better? Can you do more ‘in the box’ than before?

NM: No, not really. Sure I can do more things ‘in the box’ but it’s just a different way of working. I still have the same tasks to do. I just use less outboard gear than I used to. The Focusrite compressor for example is pretty much redundant these days for me, unless I want to compress something at the time of recording, like vocals or acoustic guitar for example.

GG: Do you have one instrument or plugin that you love more than anything else?

Nathan's expanded Roland JV1080 synth racks (Photo: Michal Odehnal)

NM: Not really. Not a single instrument or plugin, but a single piece of kit it would have to be the JV1080. I use it for everything. It is my work horse, and I know it inside out.

GG: Making music for videogames must surely be a competitive market these days. What advice do you have for people reading this who wish to get into this specific industry?

NM: Firstly, you need to get your showreel organised. I would suggest 5 to 10, 30-second excerpts from music that you have written and produced. Audio Directors are busy people and most of them don’t have time to sit through an album’s worth of material. 10 x 30 seconds is 5 minutes, and that’s about all the time they have. Put your best track on first.

Also I should stress that this industry is mostly about who you know, so networking is a crucial step to getting your foot in the door. Go to games conventions and make friends with as many game producers and game designers as you can. Buy them pizza and beer and be enthusiastic about what they are working on, and how you would love to be involved. Ask if there is anything you can do (for free) to help move the project forward in the early stages. They will welcome the help, and if you write a good tune in the early stages, it will have a chance of sticking and then hopefully they will ask you to finish the project. Then you can start talking about money. There is no right or wrong amount, don’t pitch too high and scare them off, particularly if it’s your first job. It’s more important to get the job, but don’t pitch so low that you can’t survive the project.

GG: Finally, Nathan, what is next for you and the Tomb Raider Suite?

NM: With the Kickstarter campaign practically finished now, we just have the San Francisco Composer Buffet Reception to hold, which we will be organising next. After that I will be able to divert my attention to what I always wanted to do which is to take the live concert of The Tomb Raider Suite around the world. We already have our next show lined up in Paris for next year, with further shows in negotiation for England, Australia, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, America and Tenerife. Sidelining all this is our TV documentary about the making of The Tomb Raider Suite which we hope to complete around the middle of next year. So there’s a lot to keep me busy and to get excited about.

GG: Nathan, thank you very much for talking with me! It’s been a real pleasure.

NM: Thank you Ray, I’ve really enjoyed it.

Next year will see The Tomb Raider Suite spread its wings further with more live shows and a forthcoming documentary. It's surely an exciting time to be a fan of Tomb Raider and indeed its music! We look forward to hearing more news about live shows and events. Keep an eye on the Tomb Raider Suite website for news and more.

It is a fantastic and rare privilege to see behind the curtain like this, on a body of music with such cultural significance. We'd like to thank Nathan for his time and generosity in sharing his story with us.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Until next time,

Ray McClelland